Joint Statement on H.R. 1 by APAMSA, SNMA, LMSA, AMSA, SOMA, and MSDCI

On May 22, 2025, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 1 One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which contained disconcerting provisions aimed at cutting Medicaid funding by almost $700 billion over the next decade. Medicaid has been a central fixture for 83 million Americans, providing essential healthcare and long-term care for children, seniors, people with disabilities, and low-income adults. The Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion to adults who earn up to 138% of the federal poverty level ($21,597 for a single adult) has insured millions of Americans with health coverage. These potential changes will deprive over 10 million Americans from healthcare coverage through Medicaid and disproportionately affect communities of color.

Medicaid has been linked to increased access in rural and disadvantaged areas and improved health outcomes like decreasing all-cause mortality by almost 2% and lowering maternal mortality. In a recent report authored by the Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and other national health organizations, Medicaid is the primary source of healthcare for almost 30% of people of color.

Medicaid has consistently enjoyed broad bipartisan support. A recent poll demonstrates that most Americans—Democrats, Republicans, and independents alike—favor maintaining and increasing spending on Medicaid access. Forty states across the political spectrum have opted into Medicaid expansion, recognizing the program’s role in improving health outcomes, supporting rural hospitals, and reducing uncompensated care. Despite the overwhelming evidence that Medicaid is extremely popular across the political spectrum and saves lives, House Republicans have moved to sacrifice public health in favor of funding tax cuts that primarily benefit the wealthy. The harmful provisions in H.R. 1 stand in contrast to the values shared by voters of all political backgrounds who believe Americans should not be denied care due to their income.

The bill will attempt to cut costs by

- Reducing the incentives and federal subsidies given to states for expanding Medicaid, specifically punishing any state that provides any health benefits or assistance to undocumented immigrants with lower expansion matches,

- Establish cost-sharing and copays of $35 for services provided to anyone above the federal poverty level ($15,650 for a single adult),

- Instituting stringent work requirements and eligibility verifications that burdens Medicaid recipients and state governments with more paperwork,

- Prohibiting Medicaid payment to nonprofits and providers that focus on reproductive health, family planning, and abortion services like Planned Parenthood,

- Removing gender affirming care as an Essential Health Benefit under the Affordable Care Act and prohibiting coverage for any Medicaid/CHIP recipient,

- Suspending rules that streamline application and enrollment into Medicaid and for patients who qualify for the Medicare Savings Program (covers Medicare premiums and cost-sharing for low-income Medicare beneficiaries).

We strongly condemn any legislation aimed at limiting equitable access to Medicaid or attacking access to abortion services and gender affirming care. Among the many destructive changes also embedded in H.R. 1, the elimination of federal student loans and loan forgiveness programs will severely limit access for students from all backgrounds to pursue careers in medicine. This bill proposes a lifetime cap of $150,000 for federal graduate student borrowing, specifically for those enrolled in professional programs. This will potentially force students to rely on private loans with less favorable terms and fewer protections, undoubtedly compounding the physician shortages in the very communities that rely on us.

At the heart of these proposed cuts lies an uncomfortable truth – healthcare is not a human right if equal access is not afforded to everyone regardless of socioeconomic class and immigration status. These actions go against the principles set by other nations, the World Health Organization, and the EU among others, highlighting the precarious path that the U.S. government is currently steering the country down. If passed in the Senate as is, the “One Big Beautiful Bill” will greatly harm patients across the United States and hamper the ability for physicians and other healthcare providers to serve their communities.

Call to Action:

To Senators – We call on all senators to reject this bill to protect the American public’s interest and maintain our great nation’s founding principles of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness”

To Medical Students – we urge all medical students to contact their Senators in Congress and demand a No vote on the “One Big Beautiful Bill.”

Signed,

Asian Pacific American Medical Student Association (APAMSA)

Student National Medical Association (SNMA)

Latino Medical Student Association (LMSA)

American Medical Student Association (AMSA)

Student Osteopathic Medical Association (SOMA)

Medical Students with Disabilities and Chronic Illness (MSDCI)

Additional Resources:

Contact your Congressional Representatives: https://www.congress.gov/contact-us

More information about federal student loans changes: Official Statement and infographic

Call or email your Representative today with a call script from our partner organization, Vot-ER: https://go.vot-er.org/0mAQQu

For questions regarding this statement, please contact:

Rapid Response Director, Brian Leung at rapidresponse@apamsa.org

Win a Personalized, Signed Book by Ocean Vuong!

Enter to win a personalized, signed book from Ocean Vuong (unlimited entries!) to raise money for the LGBTQIA+ Scholarship for AANHPI Medical Students!

Three books, donated graciously by Ocean Vuong and his team, are being raffled off: On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Time is a Mother, and his brand new book The Emperor of Gladness!

Click here to enter!

For questions, please contact our LGBTQIA+ Director, Joey Hua-Phan (he/they), at lgbtqia@apamsa.org

Skin Cancer Screening Toolkit

Checklist and Links to Helpful Resources

- Review Skin Cancer Screening Protocol (also linked and described below)

- Skin Screening Training Guide

- Release Form Example

- Patient Health Information Form

- Event Sign-Up Template

- Materials List

- Community Member Demographic Collection

- Additional Resources and Links

Screening Skin Cancer Protocol

For a PDF view of the protocol below, please see this link: https://tinyurl.com/APAMSASkinCancerProtocol

At least 6 months before:

- Identify a community partner. This can include any institution, community cancer center, community health center, or municipal center that is willing to collaborate with you on your event.

- Identify physician mentors. Note that this is absolutely imperative for the success of your program. You must have a licensed physician participating at the event to sign off on screening results.

- Feel free to reach out to physicians outside of your institution. Working with community partners is strongly encouraged.

At least 5-6 months before:

- Research follow-up care options and referrals to the necessary practitioners as needed.

- Secure event location, obtain funding, gather educational materials, and print necessary health forms.

- Stay tuned for the release of our APAMSA Cancer Screening Grant to aid with funding.

At least 2 months before:

- Promote your screening in local newspapers, grocery stores, churches, and other areas in your community.

- Have online sign-up forms prepared and advertised so that clients can schedule an appointment.

- Start gathering all necessary materials (PPE, gowns, penlights, etc.).

At least 2 weeks before:

- Recruit and train volunteers – roles may include navigators, room turnovers, and desk clerks at check-in/check-out stations.

- Determine volunteer schedule. Go over protocol with them.

Day of screening:

- Volunteers hand out educational materials, register clients, and collect the proper forms (release forms, health info, self addressed envelopes).

2-3 weeks later:

- Contact everyone who participated in the screening via letters or phone calls regarding their screening results.

- Follow up with community partners and debrief on the event.

- Complete and submit Event Feedback Report to the APAMSA Cancer Initiatives Director.

Please contact cancer@apamsa.org in advance if you will be organizing a screening program and would like to participate in the national APAMSA effort to increase community access to cancer screening and education.

A full list of links to find healthcare access aid resources in your local area along with multi-language materials to utilize at your event can be found here.

Step-by-step protocol:

- Identify your population or community of focus. We highly recommend reaching out to local community organizations to discuss partnership.

- Identify a local physician (primary care, dermatologist, oncologist) who will serve as your mentor and oversee the screening.

- Important point: It is absolutely imperative you work with a physician for your program. Reports given to screened subjects must be signed by a physician.

- The American Cancer Society offers a list of databases to help allocate physicians in your area.

- Determine the cancer outreach and language needs in your area. Refer to this collection of multi-language cancer awareness pamphlets for examples of resources.

- Note: It is important to implement resources and an action plan that are inclusive of diverse skin tones and colors.

- Identify materials needed for the screening: Feel free to refer to this Materials List as a guide. Quantity and costs are subject to change.

- Secure funding to cover the cost of materials. APAMSA is setting up a Cancer Screening Grant application, so stay tuned for opportunities to gain funding.

- Research the following questions.

- Where can insured screening-positive clients obtain care?

- Provide referral information for physicians who see clients with suspicious skin lesions. The client’s own PCP is also sufficient.

- Where can uninsured screening-positive people obtain care?

- Provide information regarding clinics for the uninsured – find community health locations using this link.

- Are interpreters needed for your event?

- You may need to seek peer educators or AANHPI advocacy groups to recruit multi-lingual volunteers to serve as patient navigators, since many community health clinics do not have resources for interpreters for many Asian languages.

- Refer to the Additional Resources document for interpreter resources if needed.

- Where can insured screening-positive clients obtain care?

- Develop a client follow-up plan

- How will you ensure that clients who need further follow-up are able to contact any referrals made?

- E.g. additional phone calls to make sure the clients have contacted a primary care provider or have made an appointment.

- How will you ensure that clients who need further follow-up are able to contact any referrals made?

- Identify an appropriate screening location.

- This can be at a clinic that sees Asian patients, a cancer institute, a church, community center, or your local campus. For your screening event to go smoothly and efficiently, it is recommended that your venue has a waiting area, an area for check-in, at least two or more private rooms with seating, an area for check-out, and plenty of hallway space for multiple people to walk through.

- Obtain educational materials in English and Asian languages regarding skin cancer to distribute to the clients who come to your screening. Use existing materials from the CDC, American Cancer Society, The Skin Cancer Foundation, the American Academy of Dermatology, etc.

- Refer to this collection of multilanguage cancer awareness pamphlets for examples of resources.

- Print and organize all necessary forms: Our cancer screening toolkit contains examples of release forms and patient health info forms that you may utilize.

- If applicable, consider the need for translated versions of these forms based on the population you serve.

- Recruit and train volunteers; these may be students or members of community partner organizations. For a screening event that lasts multiple hours, you may assign hourly shifts to volunteers.

- These volunteers will be responsible for turning over rooms, serving as navigators, working at check-in and check-out stations, and some may participate in performing skin exams with a physician’s oversight. Assign a lead volunteer to be in charge of rooming and collecting forms.

- Advertise your event to members of the local community. Create registration forms that request contact information of clients who are scheduling an appointment. You may also request contact information of the client’s primary care provider (if applicable) to send results directly to them after your screening event. Distribute fliers to communal areas like grocery stores, churches, or recreational centers. See examples of fliers provided in our toolkit.

- Send out a reminder to all registered participants a week to a couple days in advance of their appointment time and event location.

-

- Have student volunteers ready at different stations.

- a. Check-in: Have clients fill out a health info form and a release form – see examples in our toolkit. Inform the client to take these two forms with them to the exam room. Keep an organized log of every client, their appointment times, and contact information to keep track of all clients who present to the screening. Have seating, clipboards, and pens available for those who are filling forms or are waiting to be seen.

- b. Screening Station: Each room should be turned over and prepped for every new client to be seen. A complete room should have all necessary PPE (gloves, masks, hand sanitizers), measuring tape for recording suspicious lesions, a clipboard and pen for the examiner, and a fresh gown for the client. Make sure each client is given plenty of time to change before being seen by an examiner.

- Use colored indicators on doors to track the status of each room: (1)vacant and ready for a new client, (2)occupied with a client who has yet to be seen, (3)occupied with both client and examiner, (4)vacant but needs to be turned over. You can use a binder ring with four different colored construction papers placed on a hook or doorknob.

- You should assign a volunteer as a lead who is in charge of rooming. This person assigns clients to vacant rooms and allocates an examiner to each client who needs to be seen. After each visit is complete, the lead should collect all Release forms from the client, and direct the client to a navigator to be escorted to check-out. The client should have only their Patient Info Form with them at check out.

- You should assign additional volunteers as navigator or room turnovers. Navigators are to escort clients from check-in to their screening station and back to check-out. Navigators should also double check that all client forms are handed to the lead. Room turnovers are to keep all rooms stocked with supplies and prepare a new gown for each client.

- Have student volunteers ready at different stations.

- Check-out: It should be recorded when each client has finished their screening and left the facility. Make sure to scan a photocopy of each client’s Health Info Form; they can take the physical copy with them for their own records or if they choose to present it to their provider at a follow up visit. At this point, volunteers can double check with the client that their logged contact information is correct in case you would like to follow up with them. Also confirm with the client that their PCP information is correct, or if they require referrals based on their insured status. Inform the client that their screening results will be sent to their established provider if they have one.

Overview of Screening Responsibilities:

- Positive for a suspicious lesion

-

-

- Recommendation: further testing, referral to a primary care physician, or follow-up at a clinic that accepts uninsured clients.

- For insured clients:

- Identify a physician/physicians in your area who specialize in skin cancer (dermatologists). Refer clients to these physicians, or encourage them to make follow-up appointments with their own primary provider.

- For uninsured clients:

- Ideally, identify and refer clients to a community health center dedicated to the Asian population.

- If unavailable, refer to a community health center, a clinic for the uninsured that provides Asian language services, an established navigator system, or a student run free clinic affiliated with your institution. Be aware of what referral systems and services are offered at your student run clinic.

- For insured clients:

- Recommendation: further testing, referral to a primary care physician, or follow-up at a clinic that accepts uninsured clients.

-

- Negative for suspicious lesions

- Recommendation: Encourage education and promote awareness.

-

-

- Educate clients that a negative screening result does not eliminate the possibility of skin cancer. Inform them of risk factors and prevention methods. Emphasizing sunscreen use is crucial. They should also be encouraged to perform self-examinations at home to identify any new or changing skin lesions which they can bring up to their primary care physician.

-

Client Follow-up Protocol:

- All clients with an established primary care physician should have their Health Info Form sent over to their provider’s office.

- It is ideal to follow up with everyone who participates in your screening to educate them about skin cancer and direct them to appropriate avenues for treatment.

- Important point: simply telling clients at your screening event to go see their primary care physician is not as effective as calling and writing to them directly.

- With direct communication, we can ensure that 1) clients understand what they need to do, and 2) they understand the reasons for doing so.

Examples of Client Follow-up Systems:

- Letters

- If you send out letters to your clients, make sure they are in English and appropriate Asian languages.

- Ensure that the language you use is readable and accessible to people with all levels of literacy. Avoid unnecessary jargon.

- Make sure your letters are customized with information regarding clinics, referrals, and skin cancer info.

- TIP: When you register people for the cancer screening, have them self-address an envelope to themselves that you will use to send them their results. This will minimize mistakes in mailing addresses.

- Letters and Phone calls

- Sending letters and following up with phone calls is a better way of making sure the people understand their screening results.

- Make sure that if you make phone calls you have people who can speak the language of the person you’re calling, either through recruiting volunteers who speak other languages or using phone interpreter services.

- If you mail a letter, try to follow up with a phone call 2 weeks later to make sure they understand the letter and encourage follow-up. Then, make a follow-up call 3 months later to see if action was taken. The downside to making phone calls is that you can’t give medical information to anyone except for the person you screened, so you may have to call back several times.

Handling Patient Info:

- You should keep all physical copies of signed Release Forms on file for proof of HIPAA compliance. Any client is allowed to request a copy of their Release Form.

- All clients should leave the event with the physical copy of their Health Info Form after you scan a photocopy and store it digitally in a private location. Ensure that only your institution, club executive board, and/or partnered organization’s administrative members have access to these documents. You may send copies of Health Info Forms to your clients’ primary care physicians with each client’s permission.

- Make sure to discard all physical copies of sensitive documents appropriately if they are no longer needed (i.e. by paper shredding).

It is recommended before you proceed with anything to talk to your schools and partnered organizations regarding the best way to handle this.

While there is very little risk involved with skin cancer screening, every institution and health organization has different policies which you must understand before proceeding with any service that informs patient care. This is another reason why the first and most important step is to secure a licensed faculty/ physician advisor to oversee your screening.

We’d love to hear about your experience using this toolkit! If you have any thoughts you’d like to share regarding what we’ve done well and where we can improve, please fill out this feedback form.

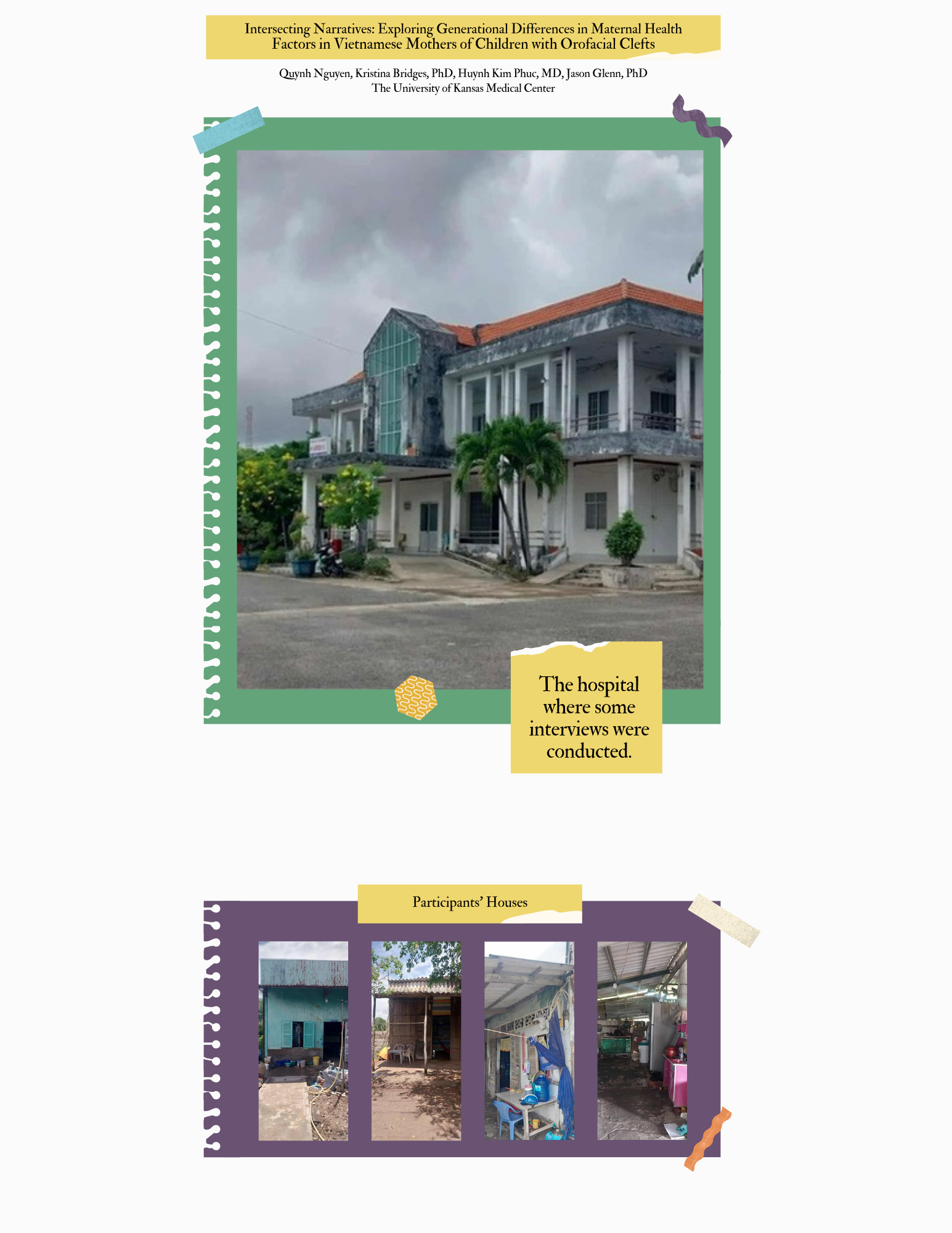

Intersecting Narratives: Exploring Generational Differences in Maternal Health Factors in Vietnamese Mothers of Children with Orofacial Clefts

Clefts Without Borders

The voices of the women I interviewed will stay with me for a long time. They’ve reshaped how I think about healthcare, equity, and the role of a physician. And they’ve deepened my commitment to becoming not just a doctor, but a better listener, advocate, and bridge between cultures.

Quynh Nguyen, MS3 at The University of Kansas Medical Center

Women in Medicine Conversations: KAN-WIN

KAN-WIN is a culturally specific nonprofit organization based in the Chicago area that serves Asian immigrant and Asian American survivors of gender-based violence. In this Women in Medicine Series episode, Abbey Zhu from KAN-WIN discusses the services KAN-WIN provides, challenges that AANHPI survivors of violence face, and how health care providers can learn and provide trauma-informed care for their patients.

Listen here:

YouTube

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

This episode was produced by Anne Nguyen, Eujung Park, and Ashley Tam, hosted by Anne Nguyen, and graphic by Callista Wu and Claire Sun.

Time Stamps:

00:00 Introduction to Women in Medicine Conversations: Abbey Zhu from KAN-WIN

00:55 Introduction to Abbey Zhu and KAN-WIN

02:21 Unique Challenges for AANHPI Survivors of Violence When Seeking Support

06:11 How to Start Conversations with the Community

11:32 Creating a Safe Space for Patients

15:18 Recommended Trainings to Learn Trauma-Informed Care

17:55 Misconceptions About Trauma and Its Impact On Patients’ Health

21:19 Policies to Improve Trauma-Informed Care

24:42 How to Connect with KAN-WIN

25:47 Wrap Up

Full Transcript:

00:00 Introduction to Women in Medicine Conversations: Abbey Zhu from KAN-WIN

Anne: Welcome everyone to a new episode of the Asian Pacific American Medical Student Association Podcast. From roundtable discussions of current health topics to recaps of our panels with distinguished leaders in the healthcare field, to even meeting current student leaders within the organization, this is White Coats and Rice. My name is Anne Nguyen and I am the Women in Medicine Director at APAMSA. I’ll be your host for today. Today we’ll be meeting with Abbey Zhu from KAN-WIN as part of our Women in Medicine Series in the APAMSA Podcast. In this podcast, we dive into topics ranging from experiences as an Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander (AANHPI) woman in medicine, to broader topics like women’s health advocacy. Abby will be sharing with us today about KAN-WIN’s mission and their work in working with domestic violence survivors and other survivors of violence within the AANHPI community.

00:55 Introduction to Abbey Zhu and KAN-WIN

Anne: Hey everyone. So we’re here today with Abbey from KAN-WIN. Abby, could you go ahead and introduce yourself first and a little bit about KAN-WIN?

Abbey: Yes. Hello, my name is Abbey. My pronouns are she/they and I’m the community engagement team lead at KAN-WIN. And KAN-WIN is a culturally specific nonprofit organization based in the Chicagoland area, serving Asian immigrant and Asian American survivors of gender-based violence. So what that looks like is we serve survivors of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual violence, and we have direct services available for them. So that includes legal advocacy, counseling, general wraparound case management, but we also have a super robust community engagement and outreach and education team. So we’re doing both the immediate crisis intervention work, but also trying to lay the foundations for a lot of community and social change so that hopefully we can equip all community members,

regardless of whether or not they’re working for a domestic violence agency with the skills, knowledge, and confidence to be able to support and advocate with survivors of domestic violence.

Anne: Thank you for sharing about KAN-WIN’s mission. It sounds like you all do a lot of great work within the community, especially with different multifaceted approaches, like you were saying.

02:21 Unique Challenges for AANHPI Survivors of Violence When Seeking Support

Anne: I was wondering if you could share with us some unique challenges that Asian American, Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander survivors of trauma and violence face when seeking medical or psychological support, especially because KAN-WIN has such a strong, culturally responsive focus.

Abbey: Yeah, I forgot to mention this during the intro, but at KAN-WIN, our staff speak Korean, Mongolian, and Mandarin Chinese, and we were actually founded by Korean Advocates in 1990. So this is our 35th year anniversary of serving clients in the Chicagoland area. But related to that, right, because we’re doing both the direct service work and doing the community outreach and education work, just getting a general pulse on how the community’s doing, kind of what victim-blaming attitudes they might be internalizing, and then also just the fears that survivors themselves might face in like coming forward, asking us for help, even identifying as a survivor. I think especially in a lot of immigrant communities, a lot of our communities are very tight-knit, right? We depend a lot on each other because obviously the United States is not an incredibly welcoming space for immigrants, an incredibly welcoming space for people of color. It’s so beautiful, the ways that we’re able to build these strong communities, but at the same time, because of how tight-knit they might be, there’s a really strong fear of gossip, or there might be a really strong fear of folks stepping, “stepping out of line,” and so there might be a lot of silencing or shame in identifying as a survivor of domestic violence. I think one of the most prominent issues that KAN-WIN has been addressing since our founding is even identifying or naming something as violence. When people immigrate to the US, after they get to the US, there’s so much structural, systemic, and also interpersonal violence that people might feel like they have to normalize or be okay with to literally just survive. So I think the biggest challenge is what someone might perceive as normal, actually naming it as violence and being like, “This isn’t okay.” And I think for a lot of people, too, they might have grown up in families where there wasn’t mutual respect between parents or there might have been power dynamics between parents or power dynamic between parents and children. And when there is a power dynamic, then violence might be seen as justified, right? So I think our biggest challenge has been going out into communities, doing a lot of education around healthy relationships, not just like, “How do you identify domestic violence?” but like, “How do you actually build a healthy relationship with the person you’re dating, the person you’re married to, parents and children?” And how do we talk about things like consent not just in the terms of like sex and dating, but also between family members and trying to change the norms around how we are in relationship with each other, especially while dating or within the family, and really, really pushing for that like, norms change at the community level, not only so that we build those healthy communities and families and relationships that we want to see everywhere, but also so if someone does experience violence, that they’re able to identify it, name it, and not have any fear around disclosing to people.

Anne: Yeah. Yeah, I think that because this is such a sensitive topic, a lot of the time you want to make sure that you cultivate a safe space for that person to come forward themselves and be willing to put themselves forward in a way that, like at their own pace, everything like that.

So I think like you were saying big issues are like just starting the conversation in the first place and then getting a sense of what that person even thinks is normal or what they’re like potentially minimizing in their lives.

06:11 How to Start Conversations with the Community

Anne: I was wondering for KAN-WIN, because you were talking about education and community outreach for y’all, how do you guys get people to be receptive to your efforts, or how do you start these conversations in the first place?

Abbey: Yeah, that’s such a good question. And I think it’s something we continue to try to figure out. I mean, at KAN-WIN, we have a multilingual advocacy team as well as community engagement team. So we work together, but we’re also separate departments. You can think of us as separate but partner departments. And for our multilingual advocacy program, they are people who are bilingual, so fluent in an Asian language and also fluent in English. And they explicitly do education and outreach to immigrant communities where people might not be speaking English as their first language. So we have a Mandarin Chinese speaking advocate, a Korean speaking advocate who also does a lot of targeted outreach to Korean faith communities, so Korean Christian communities, and then we also have a Mongolian advocate.

And I think it helps so much, obviously to be able to do things in language, so much of our values are also embodied in our language and that– being able to have someone who can translate and interpret so skillfully is really important. And then also I think, depending on like what generation immigrant you might be, that also is going to change your lived experience, your values, and the way that you move through the world. So I think having that team is so, so helpful because they’re generally targeting older folks, first generation folks, people who don’t speak English as their first language, and really just laying the groundwork for, okay, like, hey, like a lot of the things that you’ve experienced in life are really, really messed up. Like, a lot of them can change and can be different, especially for future generations. And on the community engagement team, we’re mostly English speaking, we have a youth and young adult organizer who explicitly does education and outreach to Asian American high school students. We focus on college students, and then also like professional to professional training, like certification training, sexual harassment training, bystander intervention, etc. But what we’ve been trying to do is try to also do more, just like intergenerational dialogue. So actually, this past February, our youth and young adult organizer, our faith advocate, our Korean speaking faith advocate, and then also members of our direct service team did a whole month of workshops and programming with Korean churches. So they did workshops on teen dating violence because February is teen dating violence awareness month. And they did workshops just for the parents specifically, just like what they should know about teen dating violence, how to support their children, how to maybe identify as well. And then for the teens themselves, our youth and young adult organizer and an art therapist on staff did workshops around boundaries, consent, basically how to maintain healthy relationships. Think about healthy relationships, both within the context of family but also dating. And an art therapy workshop that kind of also helps facilitate, ‘How do I want to set up boundaries? What kind of boundaries do I want to enforce’, etc, etc. And they also created a brochure so that parents and children could have a dialogue with each other. And so this very targeted intergenerational outreach I think was super well received. I mean it’s something that parents will always be worried about. They don’t want their children to be facing violence right. Then for children, empowering them to be able to keep themselves safe and then also set the foundations for the types of relationships that they want to have was so, so helpful. And I think like we want to keep being able to do that into the future because I think parenting workshops have been super helpful, especially among first gen immigrants, people who don’t speak English as their first language and our multilingual advocates have done consent and parenting workshops so often. And we want to be able to keep developing that and keep creating conversations between generations, just that we can like really clearly emphasize that there are folks in the community who are thinking about this who recognize that mental health is a really big issue, that creating healthy relationships is really difficult within immigrant families. And how do we start doing that, start saying like, some of these things that might have been seen as normal are actually not okay. And how do I know that other people also have my back and are going to support me and trying to create a different or better future for all of us.

Anne: I think that you brought up really great points about like the very targeted interventions because you know, this is– these are like issues that affect many people of like many different backgrounds within the same community. I like the work that you did with the Korean communities and things like that because it’s just you’re really utilizing something that is like a sense of a support system for people who are going through things and then by partnering with them, you know, you can create a much stronger and safe space for people to talk about things.

11:32 Creating a Safe Space for Patients

Anne: I think for us as future health care providers that learning how to build and create the safe supportive space is something that we’re always keeping in mind when we talk to patients. I’m just wondering if you had any tips for how clinicians or health care providers can navigate these conversations about difficult topics like violence, especially maybe in terms of language so we can approach care without actually traumatizing or just kind of like accessing the situation when we meet patients who we think might be going through something.

Abbey: Oh, that’s such a good question. And like my first instinct to answer that question is just like to be curious about your patients to ask questions that might not just be directly related to their symptoms of where they’re coming in to seek care for, but genuinely being curious about

patients’ lives and getting the context for why this person came in, in the first place. And I think just having longer conversations with someone reveals so much, especially for domestic violence survivors or really anyone who is a survivor of like racialized violence or economic violence etc. Right? What, beyond like the medical care that can be provided, maybe I can refer someone to a social service organization that could provide economic financial assistance or housing assistance rental assistance, if someone’s worried about insurance or like paying for their health care, and giving them information about Medicaid or other affordable health care options in your city or in your state. I think with domestic violence. I’m sure I’m quite sure almost every state has their own version of what might be called “40 hour training”. And that’s basically just a really intensive training where you get trained on how to identify domestic violence, identify dynamics of domestic violence, how to support survivors, and basically also how to treat survivors in a– as much as possible trauma informed way. And I know the word trauma informed is such like an amorphous like bubbly word, like what does that actually mean? But to me it really just means recognizing and acknowledging that no one ever faces violence, whether it be domestic violence whether it be medical violence again like economic violence, racial violence etc. None of that happens in a vacuum, and like understanding on a deep level that the world that we live in is so unjust and so many different ways. And so when someone comes to me because they’ve experienced violence in some way or another, recognizing that it’s never just on the interpersonal level but there are so many reasons why that person experienced violence and why they’re here today, and like trying my best to be able to be able to understand the context in which the violence happened and not just like the manifest– maybe the physical manifestations of violence in the current moment. So I think just being curious, asking questions, and trying to get as much context as possible and then if you have the time, and you can get your workplace to pay for it because it’s usually so expensive, getting 40-hour-trained is super super helpful in just getting a deeper understanding of what domestic violence looks like and how to specifically support survivors.

Anne: Yeah, I think that, what you were saying about the training and figuring out the context it’s all so important and something that we need to keep in our minds constantly. Someone might not be coming to you to tell you their whole backstory but then if you kind of like make a space, elicit information, you can, you know, then gather that context and really help them to the fullest.

15:18 Recommended Trainings to Learn Trauma-Informed Care

Anne: I’m really interested in the 40-hour-training that you were talking about I was wondering if you could tell us more about that or other resources and training that you would recommend medical students and other clinicians within this– working with this community who want to improve their ability to provide trauma informed care.

Abbey: Yeah, so the 40 hour training is specific to Illinois. In Illinois, if you want to work with domestic violence survivors in a one-on-one setting so work at a domestic violence agency, volunteer for a hotline, volunteer for a shelter etc. So if you’re looking to get 40 hours of training first before you can start working with those survivors. Basically it’s just a law that’s like we want to make sure that folks working with survivors are not going to retraumatize survivors. In New York or in other states, yeah, quite confident that there are probably other training requirements for y’all, but generally domestic violence agencies or organizations will host 40-hour-trainings throughout the year, you can register for them. So some of them are all online some of them might be 20 hours of self paced learning 20 hours of in person training, but it is a really really great way to get really really in the weeds of just dynamics of domestic violence, legal options for survivors, medical options for survivors, and also like history of the anti-violence movement as well. So it’s really like kind of like foundational training for you to be able to expand your knowledge of how to support survivors of gender based violence, intimate partner violence.

In terms of other trainings I think really just any professional trainings that you can register for that deepen your knowledge of anti bias work, just anti racism, just any trainings where you can learn more deeply about the structures and systems of our world and how they impact people on the individual level and how that’s going to impact the way they show up when they come to a hospital or when they come to a clinic or when they come to the doctors. I think there are so many really amazing organizations who provide and do trainings on that, because, again, like we grow up in a world learning so many narratives about so many different people. And so there’s a lot of stuff for all of us to unlearn, because our brains are wired to think in very specific ways and we might not even be noticing, that we’re thinking or behaving and therefore acting in a way that is actually really harmful towards other people. So yeah, those are my recommendations.

17:55 Misconceptions About Trauma and Its Impact On Patients’ Health

Anne: On that topic, then, what do you think are some common misconceptions about trauma and how it can impact patients health and well being just so we will know to look out for what we want to unlearn and things like that.

Abbey: Yeah, I think, in the context of domestic violence, the biggest misconception is that the only thing that counts as domestic violence is physical violence, so people might only be looking for physical signs of injury, whether that be bruises like choke marks around the neck broken

or whatever. But what we know as folks working in the anti-violence movement as people serving survivors of domestic violence is that domestic violence is so much more than that. It could look like sexual violence, including sexual assault, it could look like tampering with someone’s birth control forcing someone to have a child if they don’t want to have a child, it could look like emotional abuse, psychological abuse, financial abuse, not letting someone get a job, not letting someone have their own bank account, and like that doesn’t manifest physically

right but all of that trauma, even if it is like “psychological” is going to show up in the body in different ways. So a lot of our survivors might be like, “Oh, like, I’ve had chronic stomach pain for months”, and like that’s stomach pain obviously is a manifestation of like the abuse and violence that they’ve been enduring, but it shows up as this like body problem that might feel like, “where did this come from?” and also like, oh, at the same time like “that’s just a stomach ache”, right. But as y’all know, as medical professionals, as medical students, all of the violence, even if it isn’t physical, is going to show up in our bodies in different ways, whether that’s mental health difficulties or issues, whether it’s chronic pain, chronic stress, high blood pressure, headaches right? Thinking about that and then also thinking about how you never really, “completely heal” from trauma. It’s always going to stay in the body in some way or another might show up as PTSD again, might show up as chronic pain, but just like getting rid of the idea that like, things can be “fixable”, but rather empowering survivors giving them the tools, the empathy and the space to decide for themselves what they want their healing journeys to look like. And also being really honest with survivors. I think that’s something that we repeat over and over again is that we’re never going to over promise to survivors when we do legal advocacy right? Applying for a restraining order or order of protection– when we help clients apply, we’re not going to say like, “you will be able to get this for sure” right? We’re going to be like “hey we’re going to help you get this, it’s ultimately up to a judge”. And I feel like in medical context, it’s a similar thing of like “we’re going to do our best to address this and work through this together”. But again, right like there’s no guarantee that it’s going to be over or gone completely.

Anne: And so after sharing about that I do think that, like you were saying, it’s really easy for people to get caught up with these kind of “classic or typical expectations” of what like a survivor would look like. So just being like very open minded to know how people might come in with different experiences and then being honest with them I think would definitely help a lot in terms of you know how to catch people while they’re, you know, in a place where they might need help.

21:19 Policies to Improve Trauma-Informed Care

Anne: So I was also wondering if you could tell us if there are any policy or changes that you think would improve trauma informed care in medical settings as well.

Abbey: Good question. I think in an ideal world, and if there were enough resources and enough time because I know y’all are also so overworked. Every medical professional if not to get 40-hour-trained but at least to get basic domestic violence or intimate partner violence training so that they’re able to identify domestic violence survivors or if someone discloses to them, like, knows what they need to do to be able to refer that survivor to the resources or services that they might need. And then I also think just increase partnerships between domestic violence organizations and hospitals, or like medical groups. I know that there are a lot of domestic violence agencies in the Chicagoland area who have partnerships with certain hospital or medical groups in the Chicagoland area where those hospitals provide

reduced cost or just like no cost care to survivors if they were to come into the hospital requiring care after experiencing domestic violence. I also know that there are really strong referral networks so if a survivor, if someone comes into the emergency room after having experienced really severe physical domestic violence, a nurse has the knowledge and knows who to call, and can know how to speak to the survivor and ask, “Hey, like, do you want me to call a hotline with you?”. And then, since they have that like referral network and those partnerships with these DV organizations, then also medical staff know who to call. And I think also, this is more like a policy level unless on like an individual medical professional level but ensuring federally like nationwide that all people have affordable health care. And so that people aren’t afraid to ask for care. I think that is one of the biggest barriers as well like “Oh, how am I going to pay for this if I were to go in to ask for testing, screening, medication, etc”. And a big part of our advocates work at KAN-WIN too, is trying to find as much as possible, state or government assistance for our survivors because a lot of our limited English speakers or might be low income or don’t have a lot of financial independence because of the abuse that they’ve been enduring so short answer to all this is just more, more just policies for all people and then also stronger partnerships and collaborations between the medical field and domestic violence field.

Anne: Yes, I totally agree with all of that like just like the stronger partnerships like I mentioned before working within the community I think it’s so powerful, because you know like, if y’all like KAN-WIN have a great network with people that you know are seeing survivors with clients, then you know, having medical groups partner with you guys really just capitalizes on that sense of trust and can really more effectively like help you all with your mission and like approach people who are survivors of violence in a way that’s familiar to them, safer for them. And then, in addition like you were saying with the policies, especially the financial aspect that you were mentioning, I think that’s huge, just removing that burden kind of opens up a whole new world, or it makes it so that people aren’t afraid to ask for help if they need it.

24:42 How to Connect with KAN-WIN

Anne: And then, just kind of as a last question, I was wondering if you could let listeners know where they can hear more about KAN-WIN’s work. What are ways for them to get involved and any exciting kind of new services or programs that you guys are doing.

Abbey: Yeah, so best way to stay updated on our work is to follow our Instagram. Our handle is @KANWINChicago, all one word, no spaces or underscores, and our website is KANWIN.org And you can subscribe to our newsletter there, our website also regularly updates like news and updates. So, great way to stay updated on the work we’re doing.

25:47 Wrap Up

Anne: Great, thank you so much for speaking with me today, sharing with us, you know more information about how to interact with survivors of violence, especially the tips on trauma informed care and culturally responsive methods. I think this was a great conversation, I learned a lot, I hope that the people listening learn a lot too. Yeah, thank you again so much for meeting with us and sharing today.

Abbey: Of course, thank you so much for having me and coordinating this, it was an honor.

Response to Proposed Limits and Elimination of Federal Student Loans

On April 28, 2025, Congress released a draft proposal to overhaul the federal student loan system, aiming to add limits to federal student loans, eliminate Grad PLUS loans, and drastically scale back current repayment plans and loan forgiveness options. For 75% of medical students who take out federal loans to pay for medical school, these new proposed rules will stifle the training of future physicians in a nation already facing a physician shortage among a growing and aging population. Congress is also discussing changes to reduce Pell Grants, which help fund undergraduate education for low-income students, including pre-medical students.

APAMSA’s membership is made up of over 4,500 medical and pre-medical students from across the country, and our national organization opposes these alarming changes that will irrevocably damage medical education financing for tens of thousands of medical students and for the many other health profession students.

We urge students to spend 5 minutes of their time to reach out to their Congressional representative to demand the protection of federal student loans. Please send this to your fellow classmates – more people contacting means higher importance to our representatives.

To find your Representative and Senators, please use the following website: https://www.congress.gov/contact-us

We have provided scripts that you can use in an email or in a short phone call to deliver your concerns about the proposed changes. Please feel free to adjust these scripts as you wish to better express your concerns. If you have voted for the Congressional representative or senator before, please mention that as a part of your statement.

Version 1:

Hi, my name is [NAME] and I’m a constituent from [CITY, ZIP].

Thank you so much for your continued support of our medical students and the future patients they’ll serve, especially in rural and underserved communities. I’m reaching out today not just as a student, but as someone who grew up in [brief personal background] and who relies on the Grad PLUS program to afford medical school. If this option were taken away, students like me would be forced to reconsider whether they can even afford to complete their training—despite our deep commitment to serving communities in need. I remain concerned about proposals to eliminate Grad PLUS or impose borrowing caps below the true cost of medical education. These changes would severely limit access for students from all backgrounds and risk worsening the physician shortage in the very communities that rely on us. I respectfully urge you to continue advocating for policies that protect access to medical education and ensure that future physicians can continue serving the communities that need us most. Thank you again for your leadership and for considering the impact this would have on students like me.

Version 2:

Hi, my name is [NAME] and I’m a constituent from [CITY, ZIP].

I’m calling to urge [REP/SEN NAME] to protect funding for the federal student loan program and oppose the elimination of Grad PLUS loans and other loan repayment options. As a [medical student/pre-medical student] at [your school], access to federal student loans are crucial to the training of America’s future physicians. In order to provide the best care to our patients across the nation, we must be supported in our education.

Thank you for your time and consideration.

IF LEAVING VOICEMAIL: Please leave your full street address to ensure your call is tallied.

For questions regarding this statement, please contact:

Rapid Response Director, Brian Leung at rapidresponse@apamsa.org

Editor Director, Christine Le at editor@apamsa.org

Director of Organized Medicine, Jennifer Deng at organizedmed@apamsa.org

Statement on Lapu Lapu Day Festival Tragedy

The Asian Pacific American Medical Student Association (APAMSA) extends its deepest condolences to the Filipino Canadian community in the wake of the devastating tragedy at Vancouver’s Lapu Lapu Day festival. On April 26, 2025, a vehicle was driven into a crowd celebrating Filipino heritage, resulting in the loss of 11 lives and injuring over 20 individuals.

This senseless act has left an indelible mark on a community that was gathered together in joy and cultural pride. As future healthcare professionals committed to serving Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander communities, we stand in solidarity with those affected. We honor the resilience of the Filipino community and the dedication of the first responders and healthcare workers who provided immediate care and continue to support the victims and their families.

APAMSA reaffirms its commitment to fostering safe and inclusive environments for all communities. We pledge to advocate for mental health awareness, community support systems, and preventive measures to ensure such tragedies do not recur (Resolution 30.001). In this time of mourning, we offer our support and stand united with the Filipino Canadian community.

For more information on how to help, please look to Filipino BC (@filipino_bc) and at the official City of Vancouver website for more updates and ways to support the community in the future.

If you or someone you know needs support, please reach out:

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: Call or text 988 (24/7, nationwide)

Asian Mental Health Collective – Resource Directory: asianmhc.org/resources

Crisis Text Line: Text HELLO to 741741

For questions about this statement, please reach out to the National President, James Chua at president@apamsa.org, the Southeast Asian Director, Fern Vichaikul at sadirector@apamsa.org, or the Rapid Response Director, Brian Leung at rapidresponse@apamsa.org.

Personal Statement and ERAS Workshop

In this episode, Dr. Grace Kajita, Dr. Indu Partha, and Dr. Sreekala Raghavan share their expertise on crafting a compelling personal statement and navigating the ERAS application process. They discuss key strategies for standing out in a competitive residency cycle, common mistakes to avoid, and what program directors are really looking for. Tune in to hear their practical tips, real-world insights, and thoughtful advice on helping your story shine – whether you’re applying yourself or mentoring the next generation of physicians.

Listen here:

This episode was produced by Annie Nguyen and Ashley Tam, hosted by Tanvi Chitre and Mason Zhu, and graphic by Callista Wu and Claire Sun.

Time Stamps:

0:00 Introduction to White Coats & Rice: An APAMSA Podcast

1:16 Introduction to Drs. Grace Kajita, Indu Partha, and Sreekala Raghavan

3:15 Mastering Letters of Recommendation with Dr. Indu Partha

10:50 Telling Your Story Through ERAS Experiences with Dr. Sreekala Raghavan

23:26 Crafting a Personal Statement with Dr. Kajita

30:46 How Should I Approach the “Hometown” Section?

33:09 How to Use Program and Geographic Signalling

35:53 Virtual Open House Etiquette and Post-Event Follow-up

39:58 Potential Red Flags in Applications

44:18 Letters of Recommendation – What to Consider and How Many to Get

48:54 How to Find Virtual Open Houses for Internal Medicine Residency Programs

51:04 Should I Mention Subspecialty Interests in My Personal Statement?

54:33 Event Outro

55:14 Closing

Full Transcript

0:00 Introduction to White Coats & Rice: An APAMSA Podcast

Annie: Welcome everyone to the 10th episode of the Asian Pacific American Medical Student Association Podcast. From roundtable discussions of current health topics, to recaps of our panels with distinguished leaders in the healthcare field, to even meeting current student leaders within the organization – this is White Coats and Rice. My name is Annie Nguyen, a postbac at Stanford University, and a member of the Leadership Committee here at APAMSA. I’ll be your host for today!

In this special workshop episode, we’re joined by three incredible physicians—Dr. Grace Kajita, Dr. Indu Partha, and Dr. Sreekala Raghavan—to dive deep into the art and strategy behind crafting a standout personal statement and mastering the ERAS application.

Whether you’re prepping for residency applications yourself, or mentoring students who are, this episode is packed with invaluable advice, real-world insights, and actionable tips to help your story shine. From dos and don’ts to what program directors are really looking for, our panel covers it all with warmth, honesty, and unmatched expertise.

Today’s episode was moderated by Tanvi Chitre, a medical student at the California Health Sciences University and Mason Zhu, a medical student at the Georgetown University School of Medicine. Both are members of the 2024 Leadership Committee.

1:16 Introduction to Drs. Grace Kajita, Indu Partha, and Sreekala Raghavan

Tanvi: Welcome to our Personal Statement workshop. We’re so glad to have you here. And, um, we’re really glad to have our three amazing speakers who will be answering all your questions and sharing all their knowledge about the residency process. And this workshop is brought to you by the National APAMSA Leadership Committee. So hope you enjoy! So our three speakers are Dr. Grace Kajita, Dr. Skreekala Raghavan, and Dr. Indu Partha. And they’ll be talking about different aspects of the residency application and also doing a Q&A with everyone at the end. Doctor Raghavan, if you wanted to introduce yourself.

Dr. Raghavan: Yeah. Thanks so much. Um. I’m Skreekala Raghavan, I am an associate program director for internal medicine residency at Mount Sinai Morningside in West, which is in New York. I’m excited to be here and joining you guys today.

Tanvi: Thank you for having– for coming. And Dr. Partha.

Dr. Partha: Hi, everybody. I’m Indu Partha. I am also an associate program director for our internal medicine residency program here in Tucson at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. I’m super excited to be here, and I’m thankful to the organizers for putting on this event.

Tanvi: Great. We’re so glad to have you. And finally, Dr. Kajita.

Dr. Kajita: Sorry I had a little trouble unmuting there. Hi, everyone. It’s nice to meet you all. I’m Grace Kajita. I am the program director for the internal medicine residency program at Montefiore Medical Center, specifically the Wakefield Track. And for those of you who don’t know where we are, we are actually in the Bronx, New York. Thanks so much.

Tanvi: Perfect. Thank you all. So this, um, is the little snapshot of what we’ll talk about in this presentation. We’ll cover letter of recommendations, experiences, and the personal statement. And then lastly is the Q&A.

3:15 Mastering Letters of Recommendation with Dr. Indu Partha

Tanvi: So we’ll start off with Dr. Partha for the letters and rec.

Dr. Partha: All right. Thank you so much Tanvi and Mason and Reanna for the invitation. And I’m super excited to talk to you guys about letters of recommendation, I think. Um, a couple of things I’d like to go over is when to ask for these recommendations. Um, who to ask for the recommendations and what to ask them, um, to actually do for you. So I think one of the hardest things for any student is just the anxiety that is related to asking somebody for a letter of recommendation, and I wish there was a way I could tell you that, you know, this is an easy thing. I think depending on different people’s personalities, um, and their interactions with their faculty and attendings, um, it can be easier for some, harder for others. But I want to reassure all of you guys that from a faculty standpoint, we all recognize when it is, um, time for applications to be turned in, we understand and know that our students are going to need letters of recommendation, um, from us. I think those of us in internal medicine especially, is one of the core clerkships are quite, um, used to having students approach us. So I don’t think you need to worry that this is a shocker to an attending that you’re going to be asking, and so at least feel a little bit reassured in that, you know, why is it important to ask the right people and make an effort to get a good letter of recommendation is, truthfully, you really want it to be a personal and non generic letter. Um, yes, letter writers are doing a lot of letter writing during application season. Um, but there are ways and I’ll go over some of those tips that I can offer you to help you create a more– personalized letter for yourself. Because in this day and age of AI, I think more and more letter writers are incorporating AI to help them write these letters. So what is it that we, as the folks asking for letters, can do to help improve our success? One of the biggest things, though, I would advise you all, is be mindful of who you’re asking for a letter. Um, make sure that this is someone who has seen you, you know, perform your best. You want to set yourself up for success, and it’s totally appropriate when you’re first meeting an attending on a on a clerkship that you know you need a letter from is just a straight up at the end of your first day to say, you know, “doctor so-and-so, I would really like to get a letter of recommendation from you at the end of this week because I’m applying for residency and XYZ– what would you recommend or what would you like to see for you to feel comfortable writing me a very strong letter of recommendation?” Um, and that’s going to be a clear ask. You kind of want to make it, um, apparent to your writer that you’re going to ask for a letter. You want them to know what you know. If you’re applying into internal medicine or surgery or what type of residency program you’re applying to. And once you take that next step and reach out with a letter in follow up. You can most certainly be a little prescriptive on what your hopes are of what they would like, what you would like them to focus on. For instance, you might have one attending who really saw you at your best in your interactions with patients, in your clinical care. You might have another attending who you’ve done research with, who can really speak to your scientific prowess, and another one, perhaps, who you did some type of procedural elective with, who can speak to your technical skills. So it’s perfectly okay and appropriate to ask each letter writer to focus on perhaps a different aspect of your skill set to highlight for your future programs to review. So, you know, you’ve settled with doctor So-and-so that they’re going to be willing to write you a letter, so when you write them a formal request via email, it’s helpful to be ready with all the information that they would need from you. And this is that kind of helpful information. You want to send your CV. You want to send a personal statement so they understand all that you have done already, what your personal statement and your ideology is. I know you guys will be getting some good tips here on what to include in that personal statement. Um, what I tell my students to include or residents when they’re applying for fellowship is, um, do you have evaluations that are from other rotations, from other classes that speak to how well you’ve done? All of that information can help show your letter writer what a well-rounded student you are. And I would include all of those. I would be very clear on what your deadline is. I would I need this letter to be submitted to ERAS by whatever my tip would be to put that deadline a week or so before your actual deadline, so you’re not scrambling towards the end. Um, perhaps ask them if it would be okay for you to send them periodic reminders. A lot of letter writers truly want to do right by their students, but just are so busy that they would actually appreciate getting some, um, reminders. And lastly, I would encourage you to provide some answers to some questions that I’ll review over to help you, um, personalize your letter. If I could get the next slide. I didn’t want to over text this, so I’m going to read these off, and you guys, if you feel like this could be of help and, you know, note them down. Um, I want to credit Dr. Kimberly Manning for, um, this idea. I’ve used it a lot for my letters that I’ve written, and it’s really helped me, uh, create some personalized letters. What I would do is when you write to your letter writers, you can tell them, you know, my mentor suggested I provide you some of these answers to help you in your letter writing to make it easier for you. Um, and the questions I have for my students answer is: “what are your strongest attributes and what are you most proud about yourself? Um, What have you done that could set you apart from other applicants? How would your peers or teammates describe you? What would you want to make sure the programs know about you and your candidacy? And then this is an optional one – what hardships, um, if you’re open to sharing, have you experienced that might cause you to be misunderstood? Again, totally optional and different students have different experiences. And lastly, three words you would like to see in your letter in support of your candidacy.” Um, if you provide answers to this and send it to different letter writers, just a reminder, please change your answers for each letter writer so they’re not all writing the same letter for you. But I have found utilizing my students answers to be very helpful for me personalizing their letters. Um, my last thing I would say is this isn’t the time to be humble. Utilize impactful words and language and be clear about what you’re proud of and what you have done. Um, this isn’t the time to, uh, sort of downplay your skill set, because this is your chance for your letter writers to advocate on your behalf. Thank you very much.

Tanvi: Thank you so much, Doctor Partha, for all of that.

10:50 Telling Your Story Through ERAS Experiences with Dr. Sreekala Raghavan

Tanvi: Next we have experiences from Doctor Raghavan.

Dr. Raghavan: Thanks so much again. Thank you for having me here. This is you know, the section about experiences in ERAS has changed over the last number of years. And so I think the way that programs have been using this section has evolved over time. And so I anticipate a lot more questions will come up than just what I’ve answered here. But what I’m really going to talk about. Um, before the Q&A at the end is what should you really include in your experiences? What should you consider leaving out? Um, and in that ERAS section, what are the most meaningful experiences mean, and how do you select which ones they’re going to be? And then what– you know, what are really– what are what’s really being sought, uh, in that impactful experiences session, which is different than most meaningful. So, you know, you can probably guess that they’re looking for different experiences that you’ve had in, uh, in the ERAS- in this ERAS section, and that includes a bunch of pre-selected categories that you can select through, uh, the ERAS application itself. I’ve kind of highlighted some of them and combined some of them a little bit here, but a lot of them are the activities that you’ve taken on potentially as clubs or extracurriculars while you’ve been to medical school. Um, a lot of folks talk about the work that they’ve done. As it’s become increasingly popular to take time between medical school and residency, and some folks may have worked as a scribe or done their certification to be an EMT and worked as, uh, as an EMT, even customer service roles and and roles that are not directly related to medicine and the medical field are, you know, can highlight a lot of really amazing things about you, characteristics that you have or skills that you’ve built while doing that job. Um, and so these are kind of the, the larger areas that you want to talk about. Some particular things for– I’m not sure exactly sure who is in the audience– so just to point out, uh, for folks who either took a lot of time off between, um, college and med school or you’ve had a little bit of a, um, like you don’t have a standard 4 year timeline for medical school, you want to be sure to use your experiences to really build in the timeline. So this very often applies to folks who are going to medical school outside the US and uh, and coming to do residency in the US, where they may have graduated medical school some time ago also, and have some years, um, in between. So if they’ve done clinical experiences in the US as observerships or, um, any externships, hh, they should definitely list– you should definitely list all those experiences because as a, you know, on the program side, what I really want to know is what’s been happening during all of this time in between and what how are you learning and growing and changing and then kind of beyond that, um, what you’re really using this section to do is to highlight who you are. What are you passionate about? Um, you know why medicine, right? So you’re going to talk about why your particular field, why you went into medicine in general, um, in your personal statement. But this is where you kind of highlight all the activities that led up to that, the kind of evidence behind all the, uh, the larger statements that you make in your, in your personal statement. And when I’m reviewing experiences, I really want to know what you’re passionate about. So then, you know, you’ve done quite a lot of things, I’m sure, over, over the last number of years. So how do you decide which are the ones that you’re going to include? You can only include ten, and you can only mark three of those ten as your most meaningful experiences. So I would you know, when you’re really thinking about which those ten are, you want to highlight things that highlight that passion, right. And you want to choose things where you’ve really shown some sort of a commitment. You certainly want some if you have had leadership positions, for example, these folks, lovely folks who are running this workshop today as part of APAMSA leadership. So highlighting that, um, type of, uh, work that you’re doing through– or service that you’re doing rather– um, through your activities is really, uh, a way to, to separate yourself, right, to, to show how unique you are, uh, in your application. Hobbies? Also, I don’t have it as a separate section here, but hobbies do fall into this experiences section. Sometimes, uh, hobbies or work or significant activities, especially for medicine before your life in medicine, um, matter. So if you were, um, like a concert violinist for a bunch of years before you really got to this point, it highlights a lot about who you are– dedication, um, different skills that you build, um, potentially around problem solving, around dependability. Um, and so all of those characteristics that you want to show, if you want to show that those are the things that you’re strong in. And these activities can help you to highlight that. Um, this is not a CV. Uh, and so just to remember that, uh, you really want to pick these, these things that highlight exactly what– what helps you stand out from the, uh, larger pool of applicants. So then how do you move into selecting your most meaningful three? Answering those questions that, um, that I mentioned a little bit earlier, like: “Who are you? What are you most passionate about? And which were the activities that helped you grow the most?” That’s also really, um, impactful when I read it. Not impactful in the ‘Most Impactful’ on the experience that I’ll talk about a little bit later. But, um, when I’m reading an application and I see that, uh, somebody has a clear theme in the things that they’ve found to be meaningful, that they’ve really grown a lot, um, participating in particular activities. It helps me feel out whether this is somebody who’s going to thrive in my residency program environment or, um, not maybe enjoy taking care of the particular population that we take care of, um, or not, or want to focus on some of the additional opportunities that exist within my program. So I’m really looking, not just for somebody who qualifies kind of on paper as like a top student. I’m looking for somebody who really wants to train with me and wants to be in the environment that my residents are in. They’re going to have a great time and learn a ton of medicine and be great at the end of it. So those are, you know, the showing your growth through your meaningful experiences, I think is a really great way to highlight who you are and how you fit in your particular, um, learning environment.

Dr. Raghavan: So what do you not want to include? Um, this is not a place to list and to have an exhaustive list of every single thing you’ve ever done. Um, some of the questions that often come up are, should I include things I’ve done in college? Yeah. I mean, if you did something for four years in college, you showed a real commitment to it. You had a leadership position in it, or you did something for a while between, um, between college and medical school. These are all things that you can include. So just the actual timing of it. Like the number of I mean, the year in which you started doing something is not or determines if it’s a really old activity. But if you volunteered for someone or something for three months in your freshman year of college, that does not go in your experiences section because it doesn’t really speak to who you are now as you apply for residency. Looking into like something that you participated in at one time, if that one thing was, you know, something that was really, really meaningful to you because it challenged you in a particular way and you grew, you could make a case for including something like that. But typically you want to– you want to show that you were really passionate about something and that it made an impact on you. This is not a place to list your abstracts and your manuscripts. There’s a separate research session for that, but that question does come up quite a lot when you list your research experiences, what you’re listing is what you learned through participating in research, not the abstract that came out of it, not the manuscript that came out of it, but what were you working on? What was your role? And so that was one of the other things not to include– if you really don’t remember what you did in a particular activity, it probably didn’t mean so much to you. So don’t put that down there. You will, you know, anything on your ERAS application is fair game in your interview. And so if you put down something that you’re not prepared to talk about, um, interviewers can be surprised and feel like, oh, even though you highlighted this was one of your 10 activities and you can’t really talk about it, they’ll question the veracity of the statement also. And so you don’t want to get caught out on that. And then again, not just that you don’t remember your role, but that you can’t describe the activity or the experience in detail because when questions about experiences come up, it’s often, you know, “what did you learn from that experience? How did you grow? What challenges did you face?” And you need to be able to describe all of those things to be able to to really show your passion and show how you stand above the crowd. And then finally, you don’t want to overlap everything with your personal statement or with the content that you go over, uh, typically with your student advisor that goes in your medical student performance evaluation or your MSPE. If they’re all exactly perfectly aligned, you just have a lot of repetition in your, uh, in your application. So you want to, you know, use this as an opportunity, this section as an opportunity to highlight other things about your commitments.