2022-2023 National Board

Executive Board

Donna Tran

President

Michigan State University

College of Human Medicine

president@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Madeleine Wong

Communications

Vice President

New York Medical College

communications@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Laureen Chan

External Affairs Vice President

SUNY Downstate

College of Medicine

externalvp@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

John Yuen

Health Affairs Vice President

Stony Brook School of Medicine

healthaffairs@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Daniel Pham

Advocacy Vice President

University of Oklahoma

Health Sciences Center

advocacy@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Onyoo Park

Strategy Vice President

NYU Grossman

School of Medicine

strategy@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Syeda Akila Ally

Diversity Vice President

University of Illinois

College of Medicine – Chicago

diversity@apamsa.org

Sai Mupparaju

Membership

Co-Vice President

Sidney Kimmel Medical College

membership@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Joyce Lee

Membership

Co-Vice President

Medical College of Wisconsin

membership@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Jonathan Weng

Membership

Co-Vice President

NYU Grossman

School of Medicine

membership@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Branch Directors

Alexander Le

Interim Community Outreach Director

Texas A&M School of Medicine

outreach@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Jane Park

Interim Cancer Initiatives Director

Western University of Health Sciences

cancer@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Tiffany Guan

Bone Marrow Director

The Ohio State University College of Medicine

marrow@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Nathan Pan-Doh

Mental Health Director

Johns Hopkins

School of Medicine

mentalhealth@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Laetitia Zhang

Hepatitis B & C Co-Director

NYU Grossman

School of Medicine

hepatitis@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Jenny Yang

Hepatitis B & C Co-Director

The Ohio State University

College of Medicine

hepatitis@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Derek Shu

Hepatitis B & C Co-Director

University of Cincinnati

College of Medicine

hepatitis@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Sang Min (Kevin) Lee

AANHPI Advocacy Director

The Ohio State University College of Medicine

AANHPI@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Eric Kim

Rapid Response Director

NYU Grossman

School of Medicine

rapidresponse@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Annie Yao

Director of Organized Medicine

University of Connecticut

School of Medicine

organizedmed@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Eun Ah Cho

Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Director

A.T. Still University – Health

nhpidirector@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Monica Villegas

Southeast Asian Director

Philadephia College of Osteopathic Medicine

seadirector@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Patrick Munar Ancheta

LGBTQIA+ Director

Michigan State University College of Human Medicine

lgbtqia@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Jerry Cui

Alumni Co-Director

The Ohio State University College of Medicine

alumni@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Annie Nguyen

Premed APAMSA Co-Director

Stanford University

School of Medicine

premed@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Devon Hori Harvey

Premed APAMSA Co-Director

The Ohio State University College of Medicine

premed@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Nicole Ng

Academic Education & Research Director

VCU School of Medicine

research@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Lucy Dong

Network Director

The Ohio State University College of Medicine

network@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Ker-Cheng Chen

Social Media Co-Director

SUNY Downstate

College of Medicine

socialmedia@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Madelynn Zhang

Social Media Co-Director

The Ohio State University College of Medicine

socialmedia@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Jessica Hsueh

Database Director

Georgetown University

School of Medicine

database@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Zheng Hong Tan

Sponsorship Co-Director

The Ohio State University College of Medicine

sponsorship@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Andy Lai

Sponsorship Co-Director

Saint George’s University

School of Medicine

sponsorship@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Xiaoyu Cai

Fundraising & Events Director

University of Virginia

School of Medicine

fundraising@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Ashley Tam

National Conference Co-Chair

Oregon Health & Science University

conference@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Se-Jin (Joyce) Kim

National Conference Co-Chair

Oregon Health & Science University

conference@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Aliah Mehkri

National Conference Co-Chair

Oregon Health & Science University

conference@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Hannah Moon

National Conference Co-Chair

Oregon Health & Science University

conference@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Michelle Santo Domingo

National Conference Co-Chair

Oregon Health & Science University

conference@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Membership Regional Directors

Jennifer Lin

Region 2 Co-Director

University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry

region2@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Crystal Choi

Region 2 Co-Director

SUNY Downstate

College of Medicine

region2@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Kirsten Nguyen

Region 4 Co-Director

Vanderbilt University

School of Medicine

region4@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Adam Nguyen

Region 4 Co-Director

Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine

region4@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Dennis Yang

Region 5 Co-Director

The Ohio State University College of Medicine region5@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Cindy Ho

Region 5 Co-Director

The Ohio State University

College of Medicine

region5@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Queena Zhao

Region 5 Co-Director

University of Toledo

College of Medicine

region5@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Nicholas Wu

Region 6 Co-Director

Saint Louis University

School of Medicine

region6@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Agnes Zhu

Region 6 Co-Director

Mayo Clinic Alix

School of Medicine

region6@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Ameryl Loi

Region 7 Co-Director

University of California, Irvine

School of Medicine

region7@apamsa.org

Lyndon Bui

Region 7 Co-Director

University of Arizona

College of Medicine – Phoenix

region7@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Amelia Huynh

Region 8 Co-Director

Pacific Northwest University

College of Medicine

region8@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Rachel David

Region 8 Co-Director

Oregon Health & Science University

region8@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Theresa Bui

Region 9 Co-Director

Tulane University

School of Medicine

region9@apamsa.org

Nothing found.

Committee Members

Celeste Cravalho

Piueti Maka

Tiffie Keung

Bayley Brennan

Mingqian (Ming) Lin

Richard Lee

Diane Tran

Veronica Li

Janvi Desai

Sohana Pai

Deepa Kumar

Rodney Fong

Julie Nguyen

Nway Nway

Audrey Mannuel

Danica Vendiola

Tracy Bui

Chavy Cheng

Praveen Pallegar

Ameryl Loi

Vickie Wang

Alyssa Nguyen

Wendi Wang

Jessie Jiang

Alythia Vo

Judy Le

Anita Ho

Rodan Mecano

James Hwang

Ellis Jang

Xueying Zheng

Mia Park

Cyrus Zhou

Andy Lai

Alexander Le

Connie Zhou

Justin Jiang

Cody Columbres

Ruby Chung

Asami Takagi

Jane Park

Jessica Ngo

Isabella Liu

Zheng Hong Tan

Rachel David

Joyce Kim

Naomi Tsai

Lori Sun

Lisa Kumasaka

Fountane Chan

Kristin Zebrowski

Marissa Mayeda

Chelsea Lin

Lillian Huang

Anushka Tiwari

Angie Nguyen

Ellis Jang

Past National Boards

Tips on Being a Great Officer

-

Frequent communication is key to the success of any organization. Even when it feels like no one is reading your e-mail updates, keep sending them. Importantly, STAY IN CONTACT WITH NATIONAL APAMSA. Keep your regional directors and the national officers posted about your events. Please send in your Leadership Transition EACH time your chapter has elections. This will ensure you do not lose contact with National APAMSA.

-

Recruit First years! First years are essential for the longevity and success of the APAMSA chapter at your school. Some suggestions for increasing first year involvement:

-

Send an intro to APAMSA letter to all accepted students before they arrive in the Fall. Many schools send out packets of information to their students and often will ask student groups if they’d like to include recruitment materials.

-

Get involved with recruiting. When students come to visit for interviews or for revisits have APAMSA members get involved with some of the recruiting events, such as dinners, parties, or other social activities so people can get a feel for what APAMSA is before they arrive for medical school.

-

Have elections/appoint one or more APAMSA 1st year reps onto your executive board. Also, appoint first years to coordinate some of your projects—such as health fairs, Diwali, lunar new years, etc

-

-

Take concerted steps to promote recruitment from the South Asian and Pacific Islander community. In this regard, it may help to publicize that APAMSA is the only NATIONAL organization which provides representation for ALL APIA medical students. Also, we suggest your APAMSA chapter work with existing APIA organizations in the area, whether in terms of jointly planning events, cross-publicizing each others’ functions, or both. Locally, these steps will help you to build a stronger APAMSA chapter, and nationally, they will also serve the deeper purpose of helping to unite the community — a step that will be vital in drawing this country’s attention to APIA health issues!

-

The success of any event requires that you advertise what you are going to do to the community you’re targeting. Contact your local school newspaper or local community newspapers about your events, ie health fairs, regional conferences, bone marrow drives, Hep B projects. Getting your chapter recognized by the press is not only good for APAMSA as a whole, but the rewards for your local chapter are tremendous. The deans of your medical school will be thrilled to know that your chapter is representing your school so well. When it comes time to ask them for funding, they will take your recognized efforts into account.

-

Serving as an APAMSA chapter officer is an incredible honor. You are in a position to educate and serve your community. Remember that members of APAMSA are in a unique position to do something about eliminating health disparities in the APIA community, so please participate in our National Service Projects to eliminate Hepatitis B and increase the Bone Marrow Donor Registrants. As an organization who understands and associates ourselves with APIA cultures, we have a responsibility to use our cultural understanding and our medical knowledge to improve the health and well-being of our communities.

Statement on Texas Senate Bill 8

On September 1, Texas law SB8 went into effect, outlawing virtually all abortions 1. By allowing third-party lawsuits against clinicians that provide abortions and restricting access to vital components of reproductive healthcare, SB8 creates a coercive environment for patients and clinicians. Additionally, it would escalate the financial and logistical barriers many abortion patients already have to confront regarding their care 2.

SD8 is an example of a “heartbeat bill 3.” In 2019, APAMSA opposed the passage of “heartbeat bills” in several states 4. We continue to oppose efforts to undermine patients’ ability to access a necessary component of their health care, recognizing that these discussions and decisions ought to remain at the discretion between patients and their health care providers without undue external interference.

SD8 will likely inspire attempts to pass similar restrictions in other states 5. APAMSA encourages its members to stay informed on local state laws, and to use accurate information from verified sources, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, to guide their patients 6.

APAMSA believes clinicians should be permitted to provide comprehensive, patient-centered, and evidence-based care and counsel. This includes the full spectrum of reproductive health care services like pregnancy testing and counseling, contraceptives, and abortions. For questions or concerns, please reach out to rapidresponse@apamsa.org.

Statment on Anti-Trans Legislation

On April 6th, 2021, Arkansas overrode a veto from the governor to pass Act 626–which banned gender-affirming treatments for transgender youth. Arkansas was only one of 33 states in 2021 that have altogether introduced over 100 bills intended to interfere with the rights of trans individuals. These bills aim to ban gender-affirming treatment, forbid trans students from participating in sports, require teachers to refer to students using their biological sex, and prohibit discussion of LGBTQ issues at school.

Proponents claim that gender-affirming treatments are dangerous and not evidenced-based. Alan Clark, the state senate sponsor of the Arkansas bill, criticized that puberty blockers and hormone treatments are “at best experimental and at worst a serious threat to a child’s welfare.”

However, medical expert groups and studies say otherwise. Most professional societies—the American Medical Association, the American Psychological Association, the American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Endocrine Society—espouse the efficacy of these treatments at improving the wellbeing of trans youth. A National Institute of Health (NIH) prospective study that began in 2015 found that earlier gender-affirming treatment leads to better overall mental health. Given that nearly 1 in 3 trans youth attempt suicide in a given year, this new wave of anti-trans legislation poses an increased threat to an already marginalized community.

Our AAPI communities would also be devastated by these laws. Research from the Trevor Project, a non-profit addressing suicide prevention in LGBTQ youth, demonstrates that AAPI trans and non-binary youth are at 3 times the risk for attempting suicide compared to their cisgender peers. In 2020 alone, the organization served around 9,000 AAPI LGBTQ individuals. Another study reported that 54.7% of AAPI LGBTQ students have experienced harassment or assault due to their gender expression, and 82.3% have heard negative remarks about transgender people at school.

These chilling statistics remind us that there is more work to be done. APAMSA opposes these discriminatory laws that would severely undermine the well-being of trans individuals and their loved ones in AAPI communities and beyond. In medical education, we can advocate to our school leaders for more curricular resources and educational events concerning the foundational importance of gender affirming care. At our various institutions, we can work to establish clear, confidential pathways for transgender individuals to report mistreatment and discrimination. On a policy level, we can fight for local, state, and federal governments to recognize trans rights as human rights. We stand with the trans and nonbinary members of APAMSA and urge all our members and allies to show solidarity and advocate for the trans community in this ongoing fight against injustice and discrimination.

In solidarity,

Your APAMSA National Board

2021 National Conference

Agents of Change: Celebrating Resilience, Addressing Inequalities, and Marching Forward

DATE: January 22-24, 2021

LOCATION: Virtual at University of California, San Francisco

We are pleased to invite you to the 2021 APAMSA National Conference. Our conference theme this year is Agents of CHΔNGE: Celebrating Resilience, Addressing Inequities, and Marching Forward. Our conference will address not only the health challenges faced by the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) community, but also be tailored to current issues surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic and AAPI solidarity and advocacy. This conference is open to all community members. We hope you will join us! For more info: https://www.2021apamsaconference.org/

Contact conference@apamsa.org for questions/concerns.

Early Bird: For individuals that register before 10/17 and attend the conference in full, 3 individuals will be randomly selected and receive an Amazon gift card as raffle prizes.

We are pleased to invite you to the first-ever combined region VI & VIII Asian and Pacific American Medical Student Association (APAMSA) conference: “Shaping Y(our) Future: Diversity and Advocacy in 2020”.

The members of APAMSA have witnessed many conferences and workshops that addressed the unique educational, leadership, healthcare, and cultural barriers that members of the APIA community face in their daily lives. This conference aims to understand what our impact might look like after just scratching the surface. With medicine becoming increasingly progressive with modern technology, it is important that APAMSA follow suit in our own unique way.

The theme should lead attendees to discover intersectionalities they are passionate about and to be inspired by their peers and mentors on the possible new advancements in the field. This regional conference rallies our energetic membership to refine and guide their ability to take positive actions in our community. While the past has countless stories, advice, and memories that can never be replaced the future holds so much potential to reshape a better world than we were introduced to.

N/A

Lisa Moscoso, M.D., Ph.D.

Associate Dean for Student Affairs, WUStL

Opening

Jessica Guh, M.D.

Family Medicine Obstetrics, Seattle WA

Closing

Eriko Onishi, M.D.

Assistant Professor of Family Medicine, OHSU

Topic: Care and Cultural Diversity at the End of Life

Joe Pangelinan, PhD

Director of Cultural Awareness and Diversity in WUStL Department of Medicine

Topic: Academic careers in medicine, Under-Representation of APA/AAPI in upper management in medicine

Gordon Hall, PhD

Associate Director of Research in the Center on Diversity and Community & Professor of Psychology, University of Oregon

Topic: APA/AAPI Mental Health

Mary Anne Jackson, M.D.

Dean, Professor – University of Missouri – Kansas City School of Medicine

Topic: Infectious Disease

Angela Zhang

Medical Student at the Warren Alpert Medical School

Topic: APAMSA Anti-Racism Workshop

N/A

Contact Us

Questions? Email us at membership@apamsa.org.

.

Conference Recap

2020 has truly been a year of Change— from planning an in-person conference at UCSF to going completely virtual, the National Conference has been an undeniably unique experience. With over 550 attendee registrations, our conference connected hundreds of passionate Asian American medical students, physicians/residents, healthcare professionals, pre-health students, and community members. Without you, our attendees, and APAMSA Directors, the National Conference would not have happened at all. Again, we thank everyone so much from the bottom of hearts.

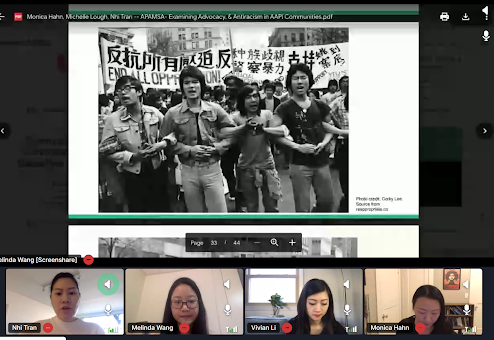

We opened with our keynote speakers, Dr. Helen Chu and Dr. Leana Wen, who enchanted our audience with their personal experiences and genuine advice for the next generation of future Asian American physicians. The day continued with multiple workshops, such as Mental Health Illness in Asian Americans with Dr. Francis Lu, Dr. Descartes Li, Dr. Hendry Ton and Finding Your Voice as an Asian American Medical Professional with Dr. Sean Wu, that focused on the critical need for Asian American leadership in tackling health disparities. And as we are trying to find our APIA identity and solidarity, Dr. Alok Patel’s workshop, Media As Your Public Health Megaphone, and Dr. Monica Hahn and Dr. Michelle Lough’s workshop, Practicing Anti-Racism, emphasized how the medical community interacts with the public and echoed sentiments of tackling social justice issues. Although this is a short, limited recap, we are eternally grateful for all of our speakers and panelists who made the effort to impart their wisdom to our attendees.

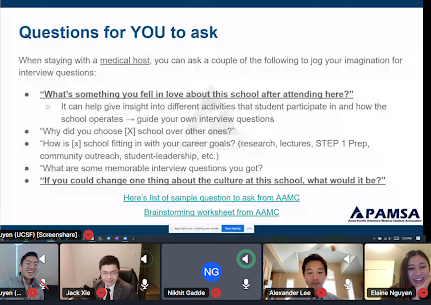

Our highlights of the Research Poster Presentations, Big/Lil Meetup, Mentoring Mixer, etc. gathered us together to celebrate scientific breakthroughs and enjoy each other’s company. Check out all our wonderful research posters on our website link (click the Research tab). The Alumni and Pre-Medical Programming served to connect our residents and physicians and future medical student colleagues. The Alumni Anti-Racism Talk explored the importance of our duty as physicians to actively combat racism in our practice and daily lives. Pre-medical students learned how to open their own APAMSA Chapters and how to ace their medical school applications and interviews.

Lastly, the Annual Elections, Raffle, and Social ended the National Conference in a wholesome way by bringing us together one last time. Congratulations to all the chapters and individuals who were acknowledged for their commitment and passion. Enjoy the APAMSA Chapter Awards Video link and Senior Service Award Video link (videos made by Linh Vu). The full list of awardees and our new APAMSA National Board are below. Thank you again to all of you, our attendees and our APAMSA National Conference Directors, National Board, and UCSF Chapter. Although we miss the National Conference already, we are looking forward to the next time we will all meet again in 2022 and hopefully in-person.

Till then, please stay safe, healthy, and happy and keep on being Agents of Change.

Lastly, the Annual Elections, Raffle, and Social ended the National Conference in a wholesome way by bringing us

If you would like to provide feedback on the National Conference, please click the following link: https://forms.gle/U3EW861mRYSm4ps17

This is optional, however we would love your input on how to improve our virtual conferences and events. Thank you!

2020 APAMSA Region 4 & 5 Virtual Conference

Shaping Y(our) Future

DATE: October 24, 2020

TIME: 8:30 PST – 2:00 PST | 10:30 CST – 4:00 CST

LOCATION: Online. Free.

Early Bird: For individuals that register before 10/17 and attend the conference in full, 3 individuals will be randomly selected and receive an Amazon gift card as raffle prizes.

We are pleased to invite you to the first-ever combined region VI & VIII Asian and Pacific American Medical Student Association (APAMSA) conference: “Shaping Y(our) Future: Diversity and Advocacy in 2020”.

The members of APAMSA have witnessed many conferences and workshops that addressed the unique educational, leadership, healthcare, and cultural barriers that members of the APIA community face in their daily lives. This conference aims to understand what our impact might look like after just scratching the surface. With medicine becoming increasingly progressive with modern technology, it is important that APAMSA follow suit in our own unique way.

The theme should lead attendees to discover intersectionalities they are passionate about and to be inspired by their peers and mentors on the possible new advancements in the field. This regional conference rallies our energetic membership to refine and guide their ability to take positive actions in our community. While the past has countless stories, advice, and memories that can never be replaced the future holds so much potential to reshape a better world than we were introduced to.

Lisa Moscoso, M.D., Ph.D.

Associate Dean for Student Affairs, WUStL

Opening

Jessica Guh, M.D.

Family Medicine Obstetrics, Seattle WA

Closing

Eriko Onishi, M.D.

Assistant Professor of Family Medicine, OHSU

Topic: Care and Cultural Diversity at the End of Life

Joe Pangelinan, PhD

Director of Cultural Awareness and Diversity in WUStL Department of Medicine

Topic: Academic careers in medicine, Under-Representation of APA/AAPI in upper management in medicine

Gordon Hall, PhD

Associate Director of Research in the Center on Diversity and Community & Professor of Psychology, University of Oregon

Topic: APA/AAPI Mental Health

Mary Anne Jackson, M.D.

Dean, Professor – University of Missouri – Kansas City School of Medicine

Topic: Infectious Disease

Angela Zhang

Medical Student at the Warren Alpert Medical School

Topic: APAMSA Anti-Racism Workshop

8:30 PST | 10:30 CST

Pre-Registration

9:00 PST | 11:00 CST

Opening Speaker: Lisa Moscoso, MD, PhD

10:00 PST | 12:15 CST

Break

10:15 PST | 12:15 CST

Break Out Session 1

11:00 PST | 1:00 CST

Lunch Break

12:00 PST | 2:00 CST

Residency Panel

1:00 PST | 3:00 CST

Break

1:15 PST | 3:15 CST

Break Out Session 2

2:00 PST | 4:00 CST

Closing

Contact Us

Questions? Email us at region6@apamsa.org or region8@apamsa.org.

Martina Leialoha Kamaka, M.D.

admin

Dr. Martina Leialoha Kamaka, a Native Hawaiian Family Physician and Associate Professor in the Department of Native Hawaiian Health at the University of Hawai`i at Mānoa, John A. Burns School of Medicine; Vice Chair of the National Council of Asian Pacific Islander Physicians; and founder and board member of the Ahahui o na Kauka (Association of Native Hawaiian Physicians) and the Pacific Region Indigenous Doctors Congress.

I am a Native Hawaiian family physician, a wife, a mother and an Associate Professor here in the Department of Native Hawaiian Health at the John A. Burns School of Medicine. I’ve been a faculty member at the School of Medicine for 20 years. I came to the medical school from private practice and although I’m a full time faculty member now, I continue to have a small clinical practice 1 day a week.

My work here at the medical school is focused on cultural competency training, and one of the things I realized, especially when I was practicing medicine in the continental US, was that culture really does matter. When I was in medical school in the 80s, I was taught to treat everyone the same and be colorblind, but I realized in practice that you can’t do that. There are differences between different groups of people such as in the ways that you communicate with them… I realized that culture was actually quite important, that was something that was downplayed when I was in medical school. And it wasn’t just communication style – it also had something to do with traditional healing practices and how that interfaces with the Western medicine system.

I’ve had some good experiences with Chinese acupuncture personally and that peaked my interest in using traditional Hawaiian medicine. I began working with our traditional Native Hawaiian healers here in Hawai’i for myself and my family and then wanted to add learning about traditional Native Hawaiian medicine to the medical school curriculum. I realized that this is an important component of healthcare, and we need to train our physicians to be open to it, to be able to offer those kinds of options to our patients, and to be able to communicate with our traditional and complementary medicine healers. We have a whole longitudinal cultural competency curriculum here and we bring in healers and talk about traditional healing practices, but we especially focus on improving student communication skills.

Finally, health disparities in our communities is a travesty. For being as advanced a society as we are, that we have these kinds of health disparities in our country is just really sad. I mean there are multiple factors that contribute to health disparities, and what I’m passionate about is making sure that students understand what the health disparities are and the possible causes for them. For example, in our indigenous communities – Native Hawaiian, Native American and Alaska Natives – the impact of colonization is huge and must be addressed. But we also have all the issues that come with our immigrant populations – they will have other reasons for their health disparities. In general, many of these disparities involve the social determinants of health, for example poverty and the way our institutions are structured. So it’s really important for students to have an understanding of the origins of health disparities. Obviously as physicians we can’t, for example, fix the secondary education system of our children by ourselves, but we have a very powerful voice as advocates.

I grew up in Hawaii in a town called Kaneohe on the island of Oahu. I got my undergraduate degree from the University of Notre Dame, in South Bend, Indiana and then I came back home to the John A. Burns School of Medicine for medical school. After that I went to Lancaster, Pennsylvania for my family medicine residency. I always thought I would come back home to practice, because I knew there was a real need for Native Hawaiian physicians, particularly female Native Hawaiian physicians. I just wasn’t sure when. I started in a small private practice in Lancaster, but I started feeling more and more like I really needed to come back home and do more. So I did come home and I was in private practice for a while when I became involved with the Association of Native Hawaiian Physicians. It was that connection that led to my current work at the School of Medicine.

You know, I just submitted a testimony to the state legislature – and that is something we can do to impact policy. I think students need to understand that when we have an MD behind our name, that is really powerful. People will listen to you. And so I think it’s important for students, especially those who come from marginalized communities, that we use our voice for our communities. We get really busy in our clinics, but we can’t separate what our patients are suffering from, from what’s going on in our communities. It’s incredibly important and we need to do what we can to try to rectify that, even if it’s just using our voice on a piece of legislation or speaking out on one policy that we’re passionate about that can make a difference in our community – if we all do that kind of thing, with every small action we take, we can be really successful collectively.

We can’t keep practicing medicine in this country the way we’ve been doing in the last 20, 30, 40 years. I’ve been practicing since 1989, and the health disparities of our communities haven’t gotten any better – in fact, some of them have gotten worse. And that shouldn’t be in a country like ours.

Being a female and a Native Hawaiian was huge because when I came to medical school, there weren’t many Native Hawaiian doctors. When I was trained – in the 80s – I was really trained in the Western model of education – very evidence-based, scientific. And then when I moved back home, and I opened up practice, all of a sudden I had a lot of Native Hawaiian patients. With that came the realization that I really didn’t know as much about my culture as I should have known. My patients were expecting me to know and yet, here I was, a Native Hawaiian who was so Western oriented.

For Native Hawaiians, we went through a cultural renaissance in the mid to late 1970s. For example, our language was almost lost. For my father’s generation, it was very shameful to speak Hawaiian. They were punished in school for speaking Hawaiian. It was also shameful to be a cultural practitioner – a lot of our traditional healing practices went underground. Then we went through this renaissance and our language came back and our cultural practices came back. I mean, we had hula before – but even that, what a lot of people thought of as hula was super different from our traditional hula – it was given a Hollywood slant. But our traditional hula came back, as did things like wayfinding (traditional navigation), eating our traditional foods, our martial arts, traditional healing practices…all of that came back. But it was around this time that I went away to college on the continent. I went to Notre Dame, and then medical school, and I was very “cocooned” in med school. I didn’t learn about cultural practices or the Hawaiian language. Remember, my father was punished for speaking Hawaiian and so he did not speak the language growing up. As a result, growing up, my family really didn’t do that many cultural things except for eating our traditional foods on special occasions as well as dancing hula and playing and singing Hawaiian music.

When I came home, there were so many expectations on the part of my patients that I was a Native Hawaiian physician, and I should know these things. When I started with the Ahahui o na Kauka (Association of Native Hawaiian Physicians) as a young doc, we tried to network with other young Native Hawaiian docs – we realized we all had the same issue, that we were raised very Western, but yet our patients were expecting more of us, and we were feeling kind of lost. We realized we needed to reconnect with our culture. We needed to connect with our land and our traditions.

I was lucky that I was able to combine this realization of the need to reconnect with our culture and land with the work that I was doing at the medical school. As the Ahahui o na Kauka got very serious about trying to help Native Hawaiian physicians reconnect to culture, my work at the Native Hawaiian Center of Excellence at the medical school was focusing on developing a cultural competency curriculum for faculty and physicians that targeted Native Hawaiians and their health disparities. We worked together – we embarked on conferences, immersions, and various activities to reconnect us as physicians to our culture, reconnect us to our land, our ancestors, our communities and also to open our minds. Traditional healing doesn’t always have “evidence” to justify how it works. All of the practices have a large prayer and spiritual component, and how do you measure that? You can’t measure that well. These are things that our ancestors have done for thousands of years and they work. For example, as Asian physicians, we don’t need someone to tell us that acupuncture works or not, we know, right?! So as a Western trained physicians, how do we bring these things together? How do we close health disparities? We want optimal health for our communities. Not just average – we want better than average. We want optimal. And how do we do that?

My first challenge was having the confidence to even think that I could be a physician. I’m the first in my family in the healthcare field, and although my father was lucky enough to go to college, my mother did not. I was the first one to get an advanced degree. I wouldn’t say my family discouraged me, I just didn’t have that confidence that I was smart enough to do it. But the thing that made me decide to go for it – apply to medical school – was that I didn’t want to be 65 and look back on my life and say, “I wish I had.” I didn’t want to have regrets. And so my attitude was, “okay, I’m gonna go for it, but I also have to have Plan B ready,” because I honestly didn’t think I was smart enough.

And I kind of struggled with that feeling of am I smart enough, am I good enough, even when I did get into med school. There were very few Native Hawaiians. And so you feel like there’s a little more attention paid to you, and you feel like you have to prove yourself. That is a little more of an extra burden and you feel like you have to work a little harder. “Yes, I belong here!” I try to work with pre meds now, and I hope I’m able to change that mindset. You have to get past the stereotypes that Hawaiians are dumb – the stuff you hear when you are little.

I was probably lucky – as a woman, I never experienced really bad gender bias. In residency, I had a couple surgeons who would call me “sweetie” or something like that, but I never really felt harassed. However, even in residency, I still felt like I had to prove myself, like “who’s this Native Hawaiian woman?” In Lancaster, they had Mennonite, Amish, African American and Puerto Rican communities – these were very different from the communities in Hawaii. But being Native Hawaiian had it’s benefits. It made it easier for colleagues and patients to start conversations with me. Luckily, people were always curious about Hawaii which made it easier for them to ask me questions and start a conversation, like “Wow, you’re from Hawaii!” Once you start a conversation with a patient, you’re already opening the door to building rapport and trust, and this makes it easier to have a good therapeutic relationship.

Also, when you’re a physician coming from a minority background – interacting with other minorities, you have something in common. You may come from a very different culture, but some of the struggles are the same. You can connect somehow, and open up conversations.

I’m active in the Association of Native Hawaiian Physicians, so I find out about issues from my colleagues when they need support. So my advice would be to get active, in your school, in organizations, or in communities back home – what are the issues coming up? What are the battles being fought? There are so many things out there – so the way you find it is to find something you’re interested in, do it, and then you’ll get introduced to more. There’s so much need everywhere!

An easy thing to do is to submit testimony. For example, there’s usually a government website for this. The hard thing is that there’s usually not a lot of time to submit it – – so you have to have an active network that will send you alerts when the testimony is needed. .

A lot of students come to medical school and already have passions from before – so you can go back to that. But if not, through rotations and electives you do get exposed to communities. I really encourage you to do at least one elective in an underserved community, because that kind of experience will really help you understand what issues affect their lives and you may find the thing you want to start advocating for.

I’m continuing my work for JABSOM in the area of improving health disparities through focusing on physician training. The IOM report, Unequal Treatment, talks about the importance of cross cultural communication in addressing health disparities… the patient – health provider communication, their interaction, is a contributor to maintaining health disparities. When we don’t know, as providers how to interact with people from different cultures, or when we have unconscious biases, those things contribute to health disparities. So it’s not just poverty, access to insurance, lack of providers, bad schools, lack of access to good jobs contributing to health disparities, but it’s also the communications between patients and the healthcare system and the providers that’s contributing. Institutional biases, our personal biases all play a role. For medical schools and residency programs, that’s one thing we can directly address – how our future providers interact with patients and to make sure that we as providers don’t contribute to the worsening of healthcare disparities and that we actually make them better.

I am very approachable by email (which I know is not the favorite form of communication for a lot of students anymore) – martinak@hawaii.edu. I’m really happy to support students, answer any questions and I am willing to help mentor. It’s one thing I didn’t have a lot of early in my training – which would’ve helped a lot with my confidence. So I’m hoping to be that person for other people!

Alka Kanaya, M.D.

admin

Dr. Alka Kanaya, a general internist, epidemiologist, and the Director of Clinical Translational Sciences Training at the University of California, San Francisco. Her research in cardiovascular disease epidemiology focuses on risk factors for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, particularly in South Asian communities.

I’m a clinical investigator and professor of medicine at UC San Francisco.

I am passionate about having representation of Asian Americans in medical research and about having data to guide our health policy and what we do in medicine, based on people who are represented in studies. And so my goal with my research is to generate data to show how different Asian American groups are – we have been aggregated in one monolith when there are over 20 different groups, and those groups are very different from each other individually! I’m in the business of generating data to make these distinctions between different Asian groups clear. Overall, my passion is to give voices to Asian American subgroups that have been neglected.

I’m the first of my family to go into medicine. I was interested in medicine primarily for clinical patient care, and I’ve been at UCSF since medical school; I chose to go into primary care because I liked having longitudinal relationships with my patients and their families, and getting to know the whole person over many decades.

Really, my patient care experiences have fueled my interest in research, because I saw many patients who were having terrible complications with diabetes as a med student and resident, many of whom were ethnic minority group members, many from Asian American communities. And we really didn’t know much about how these groups, if treatments should be tailored any differently, how to prevent these chronic diseases in the community. That just struck me as a major gap in knowledge, and I just thought we have to do something about this, because we can’t do anything without proper information.

I took a major turn in my career as a resident, when I worked on a research project to understand how we can predict TB where the sputum stain is negative, and it was a great introduction for how we can answer a question with data – it just opened up a whole new experience for me. I decided to do a research fellowship in general internal medicine also at UCSF, and I knew I wanted to focus my research on diabetes: it’s a passion for me because it is so prevalent in my family, my community, and in my patients. I have seen a lot of devastation caused by type 2 diabetes.

I found it hard to get started because there weren’t very many faculty in UCSF who do clinical research around diabetes. There’s a lot of basic science research on type 1, but not much in clinical research around type 2. So I had to cast a wide net to find research mentors outside of UCSF, and I found one at UCSD, even though it was long distance. From then it’s been a tireless effort to keep going in this track – it took a total of 5 tries to get my first grant on South Asians. Since then, I have been working on developing what we need to know, and what we can do together with this community and for this community.

It’s about disseminating the research and educating people about different ways of understanding risk factors for different groups. It’s not just about generating the data about this ethnic group that is very different than other groups, but it’s about using the data to inform the community about how to make better decisions around their healthcare and the lifestyle choices they make. And then, having that data to help guide health policy.

What we found in our study to change the way doctors and health policy makers think about risk in Asian American communities. We recently published a paper in JAMA where we disaggregated Asian American groups in a national study that’s done every 2 years, and we showed that there’s so much variation among Asian Americans and you have to disaggregate this to see who’s at really high risk for diabetes. This kind of work has really opened the eyes of many people, because Asian Americans are not thought to be high risk because of smaller and slimmer body sizes, and that’s so far from the truth – South Asians, Filipinos, and some Southeast Asian groups as well, are actually some of the highest risk groups.

We’ve also done a big Screen at 23 campaign working with the National Council of Asian Pacific Islander Physicians; when we put our data from South Asians, East Asians, and Southeast Asians together, we showed that Asians develop diabetes at a much lower BMI – 23 instead of 25, and we really need to screen Asians at 23. We had health organizations adopt this resolution that they’re spreading through their community and educating health providers about. The American Diabetes Association has adopted this guideline of using 23 as the BMI cut-point for screening Asian Americans for diabetes.

My role in medicine is to be a clinician and also be an educator to my peers and to my community at large, to help people. It’s not just about the papers you write, the citations you get, the tweets that get retweeted, or the Facebook posts that get liked. It’s about really affecting people’s lives and making them healthier.

I’m an immigrant – I was born in India and moved to the US when I was 6 years old, and I identify as Asian American. I think growing up bicultural and adopting the best of both worlds has really influenced my advocacy, because I see people who do live in both worlds or in only one of those worlds and how their culture or their society can influence their health. with that perspective, I’m able to code switch – which I do often when I’m working in the community, I can be an insider.

The challenge is constant. It’s having people take you seriously and what you’re doing seriously, and having funding for the work you want to do and having it sustained. I just received a bad score on another grant today – it’s all about persistence in this academic line of research that we’re in. You’re constantly getting bad news, tough criticism, and you have to develop resilience in the biggest way. I’m thankful to be able to laugh after a bad score now, because it’s crushed me many times! It’s all about the passion that drives you.

Get involved as soon as possible, because you don’t know if it’s for you unless you try it out – seeing what work with the community is like, what the day to day academic research life is like. Whether it’s for outreach or education, or it’s actual research recruitment or follow up, or just other advocacy work, there are so many different ways you can get involved in whatever community is of most interest to you.

Reach out to people not too far away or even those across the country – I have people reaching out to me from all over the country to spend a summer working with our group, and you can even schedule it as part of your training to have an elective month or two away. Reach out to people who you want to emulate or who you think could be a potential role model or mentor for you! And you’ll be surprised – I always respond with an email to any student or trainee, and if I just don’t have space I let them know, but we’ve taken many many student research interns over the years. It’s really about just putting yourself out there.

Well, we’re constantly working on our cohort of over 1,100 South Asians from the San Francisco Bay Area and the greater Chicago Area, MASALA – writing papers, disseminating our findings, and thinking of new ways to prevent diabetes as well as cardiovascular disease. The cohort is going to be 10 years old this year – it’s my number one biggest project.

The second new project is an Asian American research registry called CARE: we will be recruiting 10,000 Asian American community members in California who are interested in being in research that’s involved with aging, cognition, and dementia. These are Asian American groups with adults of any age, and I’m helping with the South Asian registration. The point of this registry is that when future researchers want to do research and include Asian Americans, they have a really rich registry of 10,000 names with different demographic characteristics, and all the barriers for getting better representation are lowered.

I’m on Twitter as @alka_kanaya; you can also follow the results of the MASALA cohort at @masala_study or at our website. Our website also has a great South Asian community health resources page with tips about how to stay healthy!

Kimberly S. G. Chang, MD, MPH

admin

Dr. Kimberly S.G. Chang, MD, MPH, a family physician at Asian Health Services in Oakland, California, and vice speaker of the house on the board of directors for the National Association of Community Health Centers.

I’m a family doctor at Asian Health Services [AHS], and have been working here since I finished residency in 2002. I was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawai’i. Right now I’m seeing patients part time and part time as a healthcare policy fellow at AHS – a position that we created so I could continue my policy work.

I focus on human trafficking and the healthcare intersections of that…but the broader issue is health equity and fighting for marginalized, disenfranchised populations, for their healthcare, for their equitable ability to prosper and succeed in our society. Health is a symptom of larger social problems and dislocations, and how social problems present in people’s lives is at the core of health equity and public health.

When I first started at AHS, one of my clinical responsibilities was at the Teen Clinic. We were seeing a lot of commercially sexually exploited minors – teenagers – in the Teen Clinic in 2003. And we didn’t really know what to do about these issues, what to do about these kids who were being sold for sexual services in Oakland. We didn’t have the terminology or the language. And societally, we didn’t really know what to do with it either. There was no definition for this – we used to call it “child prostitution.” Now we know that there is no such thing as “child prostitution” – anyone under the age of 18 years exchanging sexual acts for something of value is a victim of human trafficking.

Federal legislation to define human trafficking passed only 2 years before, in 2000, and policy can take a while to translate into practice. So we were seeing this on the frontline – seeing drug use, mental health problems – but… there was really nothing we could do except through the criminal justice system. We tried reporting to Child Protective Services, but because it wasn’t a caregiver perpetrating the abuse, there wasn’t anything they could do, and they referred us to the police. But the police would ask…do these kids want to report it, and they didn’t. So there was really no space where this was being addressed… What you see is a disconnect between federal and state legislation, about these definitions – of these kids as victims.

AHS started Banteay Srei as a youth development program for these youth- we were saying this is not just a medical issue. But we also needed providers to be aware, so we created a screening protocol to make sure we were catching these patients, so we could intervene, hopefully early, or even prevent exploitation and trauma.

There was a patient I saw in 2008 who ended up being really really sick and she was hospitalized for 2 months, but she really didn’t want to go to the hospital – she said she would rather die than go back to jail. That was really an “aha” moment for me, because I realized we could do all the services, all the screenings, but that was all just clinical… what were we really doing for these kids, what were they facing? How could we change the way the structures were built, change the way the systems operated, so that the youth were not afraid of systems that care and protection. I ended up getting introduced to the Director of the National Center on the Prosectution of Child Abuse from the National District Attorneys Association in Washington, D.C., and I presented all these case studies of patients I saw, saying “these kids are terrified of law enforcement, what’s going on, what can we do?”

Advocacy is a lot of media advocacy, communication, building awareness… in 2011, we got the New York Times interested in this and they did an article, looking at our programs, and how we’re seeing this as abuse, not sex work, and this is a problem for youth in our community.

So all of this really comes out of my clinical work, and based out of real people and their life experiences – patients we’ve cared for at AHS.

I mean think about it – who has eyes on what’s really going on in the community? A mentor told me this: it’s teachers because kids come to school and repeat what parents are saying in the home, pastors because they take these confessionals, and clinicians because people are sharing all of their vulnerabilities, issues, barriers affecting them and their health. If we really pay attention to our patients, not just the really narrow medical piece – but what’s really going on in their lives, the conditions creating illness and disease, you have a whole, fertile ground on which you can provide information to influence policy. That’s very powerful.

I work at Asian Health Services so I see everything through the lens of AAPI identity and experiences. I grew up in Honolulu, a majority minority state, and I didn’t really get that this was different, I was different – I just thought I was normal. I went to college in New York, at Columbia, and that was a bit more eye opening. People have ideas about who you are and how you should be, and cultural stereotypes. And that kind of opened my eyes. I went back to the University of Hawai’i for medical school, so I went back home, back to a majority AAPI location, and it was comfortable – easier to be just myself without having to worry about how people think of me. You know, there’s a tax when you’re a minority – you have to filter information through this lens, and it takes a lot of energy, and that energy could be better used and spent solving problems than trying to figure out how people see you. It’s the same thing with UCSF, where I went to residency – there’s a lot more awareness, and the mission was to serve vulnerable patients, which resonated with me.

My goal at the end of finishing residency was caring for disenfranchised patients, minorities, patients, who are vulnerable, so I wanted to see a wide variety of patients. I worked in a variety of settings after residency, and AHS was one of them. I felt like I could do more, and focus more on the patients, at Asian Health Services. Part of that was the cultural tax. AHS is very comfortable for me; even though I don’t speak fluently in another language, I think there’s an affinity with patients, of all Asian background, that we have with each other. And I think that helped with the healthcare.

I took a year off from 2014-2015 to do a Minority Health Policy Fellowship at Harvard, and this was kind of a mid career switch, and I had already worked for 10 years and directed the Frank Kiang Medical Center. Some of the personal challenges I’ve faced were coming to this awareness about systematic and structural and internalized barriers. I think for me, it was very easy to just focus on grades, school, and you’re supposed to succeed if you just follow the rules. But that’s not necessarily true – there’s a lot of Asian Americans in medicine, but if you look at the professors, deans, NIH research awards, grant awards and foundation leaders – it’s very small. Why is that?… it’s because you have to have these social connections, social capital, and it’s not just about following the rules and getting good grades. It’s about networking, lifting others up, having others lift you up, getting noticed – and sometimes, we don’t get noticed because there’s some stereotypes about Asians… A lot of times, culturally, we’re very community and family oriented – you have to make sure that everyone is doing well, not just yourself.

…The structures that we’re placed in, sometimes it’s not like that – it’s very competitive, it’s very “me or you,” and so those kinds of structures may not be conducive to promotions or things for Asians. And that’s important because these sorts of structural barriers mean less resources for underserved Asians, less opportunities, less attention to the problems faced by refugees, immigrants of Asian descent. So that’s how my personal challenges translate societally. If I am going to be a good advocate for my patients, if I can use my privilege and power effectively, I better know what the barriers are, because if I don’t at least recognize them, how would someone with much less privilege be able to overcome them?

Help each other, support each other – it’s not a “me vs. you,” it’s about you helping your colleagues and there’s an understanding that at some point they might be able to help you. The currency right now is how many groups or networks you’re a part of – information is the currency. So as many different types of groups that you’re a part of and you can get information from or contribute to, that adds to your work. Give opportunities to each other.

Look at community organizing. Advocacy is not about being the boss – it’s about the issue. What can you do to move the issue forward? Sometimes that means being the leader, and sometimes that means taking a backseat. Always keep the goal of moving the issue forward as the main priority, not your own position, not your own success. If you do this, then you will be successful.

Be intersectional – advocacy looking at other minority issues, other underserved/vulnerable populations issues – not just strictly AAPI issues. What other communities have faced and learned can be applicable to us and vice versa. Make allies.

I’m still doing human trafficking policy work – I was appointed to the National Advisory Committee on the Sex Trafficking of Children and Youth in the United States, and that’s a way to make recommendations to Congress, state Governors, and Child Welfare departments

and offices across the nation on this issue. I was elected as the vice speaker of the House for the National Association of Community Health Centers; it’s so eye opening to learn about the issues facing communities across the country – like the opioid crisis facing our partners in Kentucky and Ohio, and rural workforce challenges, among others – and I’m so proud to be working in the community health center movement.

I’m on LinkedIn and Twitter (though I’m not super active).